A photographic prelude to mass extermination by Alberto M. Melis

Many years ago, in the run-up to writing one of my children's novels, I encountered insurmountable difficulties in finding material about the Lodz Ghetto in Poland. What I was looking for were films or photographs of a specific district of the ghetto, where during the Second World War the Nazis had imprisoned five thousand Austrian Lovara gypsies, almost all of whom perished from a terrible typhus epidemic, except for a few survivors who were slaughtered in the gas trucks of the Chelmno concentration camp.

The only photograph I could find in the archives on the web showed only the entrance to the gypsy quarter of the ghetto, without any human presence. And for many years after the publication of my novel – distributed in Italy under the title ‘Il ricordo che non avevo’ (The Memory I Didn't Have) – it represented for me the emblem of a story still unknown to many, that of the extermination of the European Roma and Sinti, which in their language, Romani, is called Porrajmos (devouring) or Samudaripen (the death of all).

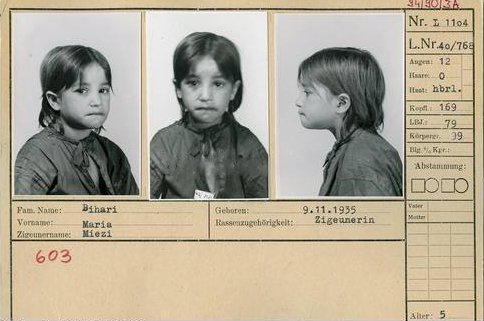

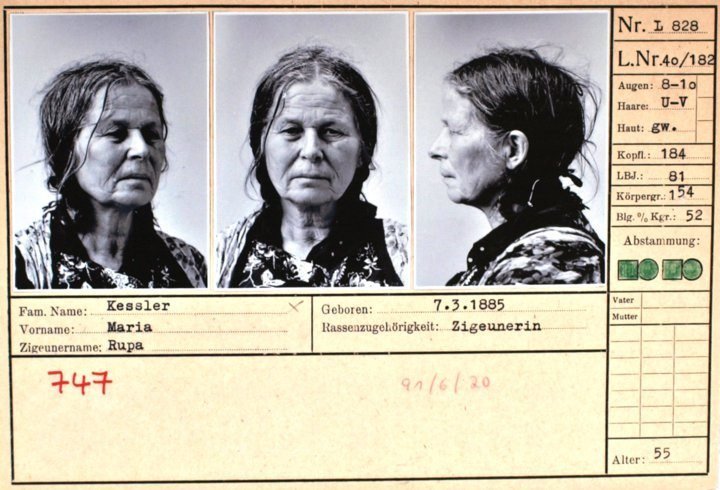

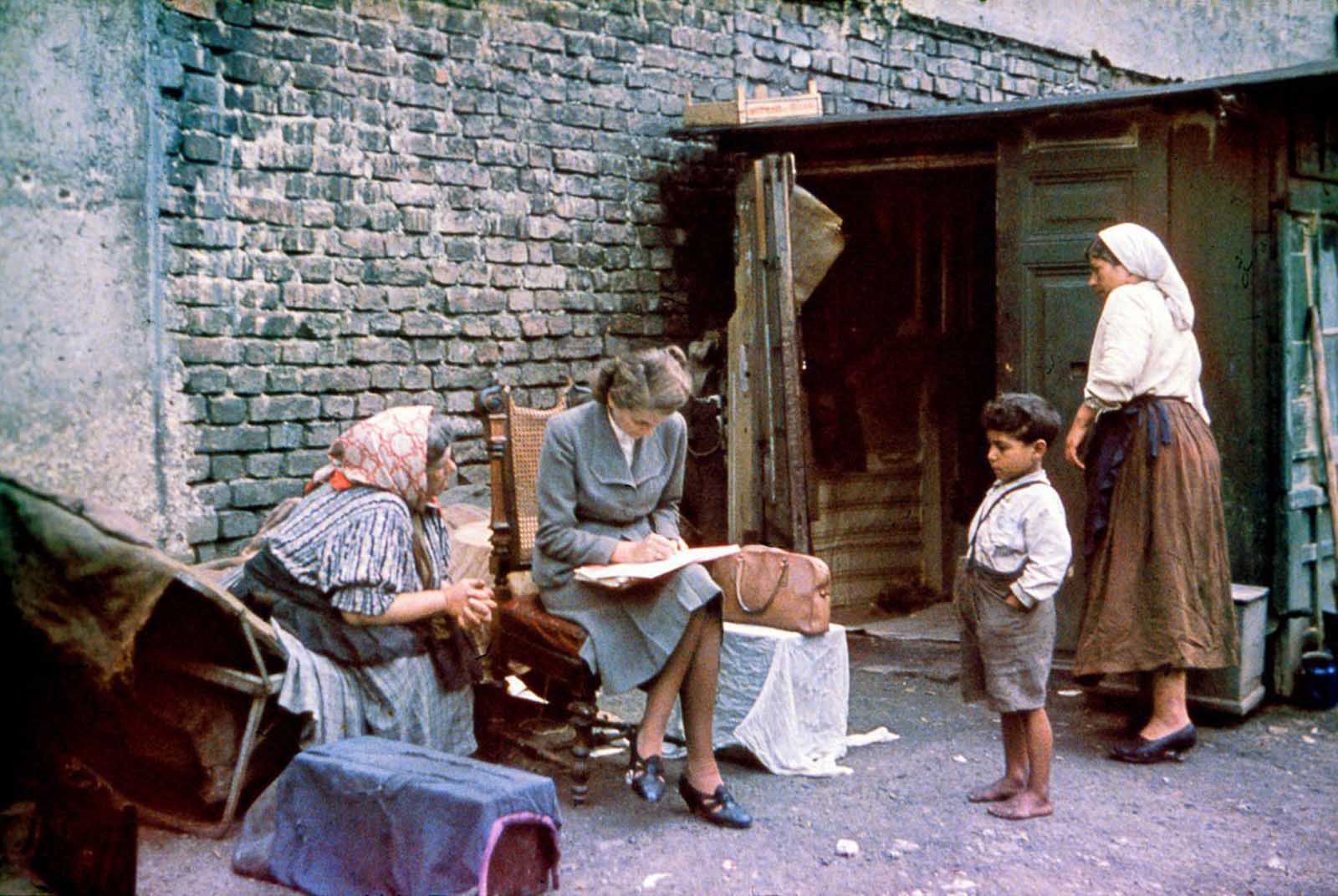

In fact, unlike the Jewish Shoah, which has been historically reconstructed not only with the testimonies of survivors, but also thanks to a huge amount of documents of various kinds, the events of the Porrajmos – Samudaripen have long been abandoned to oblivion. Also due to the lack of written testimonies and other documentary sources, including photographs. Those present in the great international archives (such as the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington or the Bundesarchiv in Koblenz) are very few. A handful of mug cards from the concentration camps, a small number of photos showing the victims imprisoned or brutalized by Josef Mengele's pseudoscientific experiments, and a few others depicting the activity of the two German pseudo-scientists, Robert Ritter and Eva Justin, who with their eugenic studies led to the death sentence of at least 500 thousand gypsies.

So imagine my great astonishment when, about a year ago, I found a profile on Facebook, belonging to a certain Stojko, which published hundreds of photographs from the years of the Second World War, with gypsies as subjects, almost all taken in the nations of Eastern Europe occupied by the Nazi army. These were not photographs showing the actual extermination, but images, equally important from a historical point of view, of the period that preceded it by a very short time.

I immediately asked Stojko, who presented himself as a Macedonian filmmaker, about the origin of these photographs. He replied that he had found them in a museum in Normandy, but he didn't tell me which museum and, immediately after, he closed his Facebook page and disappeared. Fortunately, however, not before I had saved all the photos on my computer.

I immediately sent them to some friends who have been directing or working for many years in some centres of documentation of the Shoah and Porrajmos, who confirmed their importance, but at the same time I continued to search the web for the true source of these images. Finally succeeding, a few weeks ago, in identifying it in the web pages of Robert Watson[1], an English writer and researcher, specialized in the History and Culture of the Gypsies, who over the years has collected thousands of photographs taken by German soldiers or even by the notorious SS of the Einsatzgruppen who then carried out the manhunt and massacres.

What is immediately perceived in these images, although in most of them the gypsies do not show particular fear, is the feeling of superiority of the Nazi soldiers. The gypsies, so different and miserable in their atavistic poverty and their customs, are in their eyes strange and exotic subjects to photograph. Men and children are sometimes urged to play their violins; the girls and women, mercilessly, to strip naked in front of their lenses.

According to Robert Dawson, on the back of these photographs, there are sometimes notes written by the authors of the photos. Sometimes, a few, help to understand the date and place where they were taken, and that almost never exhaustively anticipate the fate of the men, women and children photographed. Which will always be the same, death on the spot by massacre or after imprisonment in concentration camps, which will however materialize only after December 15, 1942, when in Berlin Heinrich Himmler, the number two of Nazi Germany, signed the decree ordering the extermination of European gypsies.

In order to understand the apparent paradox by which the exotic subjects to be photographed were suddenly transformed, even in the nations of Eastern Europe, into lives unworthy of being lived, we need to go back to history for a moment. The chronological path that led to the Porrajmos – Samudaripen was not the same as that of the Jewish Shoah. For the Gypsies historically came from the Punjab, a region of the Indian subcontinent, and were therefore, unlike the Jews, of Aryan stock. This was the reason that prompted Adolf Hitler, who had already imprisoned all Sinti in concentration camps in Germany, including those who had long been sedentary and perfectly integrated into German society, to order new "scientific" investigations, which were entrusted to the doctor and psychologist Robert Ritter and his assistant Eva Justin.

They, after having surveyed and studied the German Gypsies with completely unscientific and Lombrosian methods, ruled that "The instinct for research on racial hygiene is already capable of expressing itself objectively on the degree of mixture and on the hereditary value of each individual so-called Gypsy" and that Gypsies could therefore no longer be considered "Gypsies, but hybrids with the underclass of German criminals and asocial." A green light for the genocide that from 1942 flared up like a fire throughout Europe occupied by the Nazi army.

The diligent photographers thus turned into ruthless killers, and the men, women and children photographed into victims almost always destined to lie in the open air or to disappear in mass graves.

Of all the photographs that appear in these pages, two are perhaps most deserving of our attention. That of little Maria Miezi Bihari and elderly Maria Rupa Kessler, filmed in their mug shots. Probably they too, like all the prisoners locked up in the "zigeunerlager" B2E, the sector of Auschwitz reserved only for gypsies, learned from a German officer that the next day, May 16, 1944, they would all be taken to the gas chambers. And perhaps they too, the next day, when the SS showed up in the zigeunerlager, participated in what Marcello Pezzetti, a former member of the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah in Paris, called something extraordinary.

"The gypsies, practically with their bare hands, with small knives and with small improper weapons, oppose the will of the SS to carry them to extermination. Mothers lunge at them to save their children. It's something immense, something that should always be talked about in a hyperbolic way, when talking about the Resistance: because only a few other heroic acts are comparable to this."

Despite this, a short time later, the rebellion was put down by the SS and the last gypsies left alive in Auschwitz were taken to the gas chambers.

It was August 2, 1944.

Eva Justin Germania

Ghetto di Lodz

Croatia, shortly before the massacres in the forest

Children from Mulfingen on the day they were sent to Auschwitz

Un preludio fotografico allo sterminio di massa.

Molti anni fa, nella fase preparatoria alla scrittura di uno dei miei romanzi per ragazzi, incontrai insormontabili difficoltà a trovare materiale sul Ghetto di Lodz, in Polonia. Ciò che cercavo erano filmati o fotografie di un preciso quartiere del ghetto, dove nel corso della Seconda Guerra Mondiale i nazisti avevano recluso cinquemila rom Lovara austriaci, che perirono quasi tutti per una terribile epidemia di tifo, salvo pochi superstiti che vennero trucidati nei camion a gas del lager di Chelmno.

L’unica fotografia che riuscii a trovare negli archivi sul web, mostrava solo l’entrata del quartiere “zingaro” del ghetto, senza nessuna presenza umana. E per tanti anni dopo la pubblicazione del mio romanzo – distribuito in Italia con il titolo Il ricordo che non avevo - essa rappresentò per me l’emblema di una storia per molti ancora sconosciuta, quella dello sterminio dei Rom e dei Sinti europei, che nella loro lingua, il romanes, viene chiamato Porrajmos (divoramento) o Samudaripen (la morte di tutti).

A differenza infatti della Shoah ebraica, che è stata storicamente ricostruita non solo con le testimonianze dei sopravvissuti, ma anche grazie a una enorme quantità di documenti di varia natura, le vicende del Porrajmos – Samudaripen sono state per lungo tempo abbandonate all’oblio. Anche per la carenza di testimonianze scritte e di altre fonti documentali, comprese le fotografie. Quelle presenti nei grandi archivi internazionali (come l’United States Holocaust Memorial Museum di Washington o il Bundesarchiv di Coblenza) sono molto poche. Una manciata di schede segnaletiche provenienti dai lager, un esiguo numero di foto che mostrano le vittime recluse o brutalizzate dagli esperimenti pseudoscientifici di Josef Mengele, e poche altre raffiguranti l’attività dei due pseudo scienziati tedeschi, Robert Ritter ed Eva Justin, che con i loro studi di natura eugenetica portarono alla condanna a morte di almeno 500 mila zingari.

Immaginate quindi il mio grande stupore quando, circa un anno fa, trovai su Facebook un profilo, appartenente a un certo Stojko, che pubblicava centinaia di fotografie degli anni della Seconda Guerra Mondiale, aventi come soggetti dei rom, quasi tutte scattate nelle nazioni dell’Europa orientale occupate dall’esercito nazista. Non si trattava, beninteso, di fotografie che mostravano lo sterminio vero e proprio, ma di immagini, ugualmente importantissime da un punto di vista storico, del periodo che lo precedette di pochissimo.

Chiesi immediatamente a Stojko, che si presentava come un filmmaker macedone, l’origine di queste fotografie. Lui mi rispose di averle reperite in un museo in Normandia, ma non mi disse quale museo e, immediatamente dopo, chiuse la sua pagina su Facebook e scomparve. Fortunatamente, però, non prima che io avessi salvato sul mio pc tutte le foto.

Immediatamente le inviai ad alcuni amici che da molti anni dirigono o lavorano in alcuni centri di documentazione della Shoah e del Porrajmos, i quali mi confermarono la loro importanza, ma nel contempo continuai a cercare sul web la vera fonte di queste immagini. Riuscendo finalmente, poche settimane fa, a individuarla nelle pagine web di Robert Watson[1], uno scrittore e ricercatore inglese, specializzato in Storia e Cultura dei rom, che nel corso degli anni ha raccolto migliaia di fotografie scattate dai soldati tedeschi o addirittura dalle famigerate SS delle Einsatzgruppen che poi eseguirono la caccia all’uomo e le stragi.

Ciò che si percepisce immediatamente in queste immagini, per quanto nella maggior parte di esse i rom non mostrino particolare timore, è il sentimento di superiorità dei soldati nazisti. I rom, così differenti e miseri nella loro atavica povertà e nei loro costumi, sono ai loro occhi dei soggetti strani ed esotici da fotografare. Uomini e bambini a volte vengono sollecitati a suonare i loro violini; le ragazze e le donne, impietosamente, a denudarsi davanti ai loro obbiettivi.

Sul retro di queste fotografie, così racconta Robert Dawson, appaiono a volte degli appunti scritti dagli autori delle foto. Che a volte, poche, aiutano a comprendere la data e il luogo dove sono state scattate, e che quasi mai anticipano in modo esaustivo la sorte degli uomini, delle donne e dei bambini fotografati. Che sarà sempre la stessa, la morte sul posto per strage o dopo la prigionia nei lager, che si concretizzerà però solo dopo il 15 dicembre del 1942, quando a Berlino Heinrich Himmler, il numero due della Germania nazista, firmò il decreto col quale si ordinava lo sterminio dei rom europei.

Per comprendere l’apparente paradosso per il quale i soggetti esotici da fotografare si trasformarono all’improvviso, anche nelle nazioni dell’Europa orientale, in vite indegne di essere vissute, bisogna tornare per un attimo indietro nella storia. Il percorso cronologico che portò al Porrajmos – Samudaripen, non fu lo stesso della Shoah ebraica. Poiché i rom provenivano storicamente dal Punjab, una regione del subcontinente indiano, ed erano perciò, a differenza degli ebrei, di stirpe ariana. Motivo che spinse Adolf Hitler, che pure in Germania aveva già fatto imprigionare nei lager tutti i Sinti, compresi quelli da tempo sedentarizzati e perfettamente inseriti nella società tedesca, ad ordinare nuove indagini “scientifiche”, che vennero affidate al medico e psicologo Robert Ritter e alla sua assistente Eva Justin.

I quali, dopo aver censito e studiato con metodi del tutto ascientifici e di stampo lombrosiano gli zingari tedeschi, sentenziarono che “L’istinto di ricerca sull’igiene razziale è già oggi capace di esprimersi oggettivamente sul grado di mescolanza e sul valore ereditario di ogni singolo cosiddetto “zingaro” e che gli “zingari” non potevano perciò più essere considerati “zingari, bensì ibridi col sottoproletariato dei criminali e degli asociali tedeschi”. Un via libera al genocidio che dal 1942 divampò come un incendio in tutta l’Europa occupata dall’esercito nazista.

I solerti fotografi, si trasformarono così in spietati assassini, e gli uomini, le donne e i bambini fotografati in vittime destinate quasi sempre a giacere a cielo aperto o a scomparire nelle fosse comuni.

Tra tutte le fotografie che appaiono in queste pagine, due meritano forse maggiormente la nostra attenzione. Quella della piccola Maria Miezi Bihari e dell’anziana Maria Rupa Kessler, riprese nelle loro foto segnaletiche. Probabilmente anche loro, come tutti i prigionieri rinchiusi nello “zigeunerlager” B2E, il settore di Auschwitz riservato solo ai rom, vennero a sapere da un ufficiale tedesco che il giorno dopo, il 16 maggio del 1944, sarebbero stati tutti portati nelle camere a gas. E forse anche loro, il giorno dopo, quando le SS si presentarono nello zigeunerlager, parteciparono a quello che Marcello Pezzetti, già membro della Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah di Parigi, ha definito qualcosa di straordinario.

“I rom, praticamente a mani nude, con dei piccoli coltelli e con piccole armi improprie, si oppongono alla volontà delle SS di portarli allo sterminio. Le madri si lanciano contro di loro per salvare i bambini. E’ qualcosa di immenso, qualcosa di cui si dovrebbe sempre parlare in modo iperbolico, quando si parla di Resistenza: perché solo pochi altri atti eroici sono paragonabili a questo”.

Nonostante questo, poco tempo dopo, la ribellione venne domata dalle SS e gli ultimi rom rimasti vivi ad Auschwitz vennero condotti alle camere a gas.

Era il 2 agosto del 1944.