Journeying through the different worlds of imagery

Charles Harbutt

"A photograph is a collision between a person with a camera and reality. The photograph is typically as interesting as the collision is."

At my age, it often feels like I am living in a different time. I must say, I experienced a beautiful period in post-World War II Europe, particularly in Italy, where democracy was taking root and the country was starting its journey toward prosperity. When I was young, there were countless opportunities available: you could easily meet influential people, find rental homes, and enjoy a good quality of life.

However, that’s not the main topic I want to discuss. I wish to express my desire to find nearly forgotten photographers who infuse their work with depth and emotion in a world where images overshadow words and genuine thoughts seem to have faded away. For this reason, I often encounter lesser-known figures, such as Charles Harbutt, whose history and photographs resonate with me. I hope I have succeeded in gathering meaningful information and insights for you.

Charles Henry Harbutt (July 29, 1935 – June 30, 2015) was an American photographer, a former president of Magnum Photos, and served as a full-time Associate Professor of Photography at the Parsons School of Design in New York. Harbutt was a talented photojournalist known for his captivating imagery. He had a unique ability to take everyday scenes and turn them into surreal metaphors, blending art with storytelling in an incredible way.

Harbutt was born in Camden, New Jersey, and grew up in Teaneck, where he honed his photography skills through a local camera club. His father, also named Charles, worked as a traffic manager for Pepsi-Cola, while his mother, Catharine McMahon, was an amateur painter. He attended Regis High School in New York City and later graduated from Marquette University. Harbutt's early fascination with magic and the blurred line between perception and reality led him to journalism, starting as a writer.

His journey into the world of published writing began in 1955 when he shared the heartwarming story of a refugee family's escape from Europe to Michigan in Jubilee, a progressive Roman Catholic magazine. He also shed light on the lives of migrant farmworkers and civil rights issues through his articles for the magazine. He contributed to major magazines in the United States, Europe, and Japan, often focusing on politically charged topics.

In 1958, he tied the knot with Alberta Steves, though their marriage later ended in divorce. Together, they welcomed three children, who continued to carry on his legacy along with five grandchildren. In 1978, he married Ms. Liftin.

Everything changed in 1959 when, at 23, he received a unique opportunity from Cuban rebels to document the Castro revolution. Excited by the atmosphere in Havana, he realised, “I soon understood that I could get closer to the feel of things by taking pictures.” This sparked his successful photojournalism career.

Harbutt made his public debut as an artist in 1960 in the East Village of Manhattan. A reviewer from The New York Times praised his work, calling him “one of the most mature and competent of today’s young photographers,” which was quite the accolade. His captivating photography went on to grace the pages of many respected publications, including Life, Look, Paris Match, Newsweek, Fortune, National Geographic, and The New York Times Magazine. His work was also part of a travelling exhibition for the United States Bicentennial Commission and featured in "Plan for New York City," an innovative master plan presented by Mayor John V. Lindsay’s administration in 1969. His stunning photographs enhanced the writing of urbanist William H. Whyte, creating what Donald H. Elliott, the chairman of the City Planning Commission, called “a historic record—a statement of philosophy.”

Harbutt had the honour of serving twice as president of Magnum, the famous international photographers’ cooperative. He joined in 1963 and left in 1981 with a group of fellow photographers to start Archive Pictures, another exciting photo library. He also shared his passion for photography by teaching at the Parsons School of Design. Among his works are “America in Crisis: Photographed by Magnum” (1969), which he edited, as well as two monographs: “Travelogue” (1974), focused on emotional connections, and “Progresso” (1986), which tells the story of a town in the Yucatán.

Alongside Burk Uzzle, known for iconic images of the 1969 Woodstock festival, Harbutt helped reshape photojournalism, moving away from traditional styles. Jeff Jacobson, a former colleague, commented that they focused on a more creative and metaphorical approach rather than the conventional techniques of Cartier-Bresson and Gene Smith.

Despite his achievements, Harbutt faced challenges and became disillusioned with his work. After witnessing undercover government agents causing disruption at a 1970 rally in New Haven supporting jailed Black Panthers, he began reevaluating his role in journalism.

In 1997, his negatives, master prints, and archives were acquired for the collection of the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona. Trudy Wilner Stack, who organised his impressive archive, shared that his photographs eventually became "less tied to the time and place of their picture stories" and transformed into “timeless images that capture the poetry and humanity of our existence.”

His work was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, the National Museum of American History, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, the U.S. Library of Congress, George Eastman House, the Art Institute of Chicago, the International Center of Photography, the Center for Creative Photography, and at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the Beaubourg, and the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris.

In December 2000, he held a significant exhibition of his work at the Centro de la Imagen in Mexico City.

In 2004, he received the City of Perpignan medal during a retrospective of his work.

He passed away in Monteagle, Tennessee, on June 30, 2015, at the age of 79, due to complications from emphysema.

Cuba, 1959

Black Panther, 1969

Blind Boy, New York City, 1961 (Printed Later) Gelatin Silver Print Image - 12"x18", Paper - 16"x20", Matted - 20"x24"

One of his most famous black-and-white photographs depicts a blind boy who seems to be reaching for a ribbon of light on a wall, symbolically attempting to transcend his blindness.

“I became a photojournalist because I wanted to see for myself what was going on in the world. Photographers actually have to see and live through what they show, so I felt like a kind of front-line historian, getting down on paper the look of today for the future. After all, we cover peak events: wars, revolutions, famine, disease, the marauding and follies of the rich and powerful.

But I came to feel I was missing something. What about all those things that are just funny or curious or even triumphantly, overwhelmingly there? Or meaningless, banal, chaotic? What I really see in the course of a normal day. So I shot a lot of that, too.

In the early seventies, the U.S. government began to use agent provocateurs to discredit the antiwar and civil rights movements by fomenting riots to justify severe repression. The only way a photograph could show the thugs were cops would be if they wore T-shirts with “POLICE” on them. The government had become sophisticated at getting its propaganda out and I didn’t want to be a messenger. Things aren’t always what they appear to be.”

Charles Harbutt

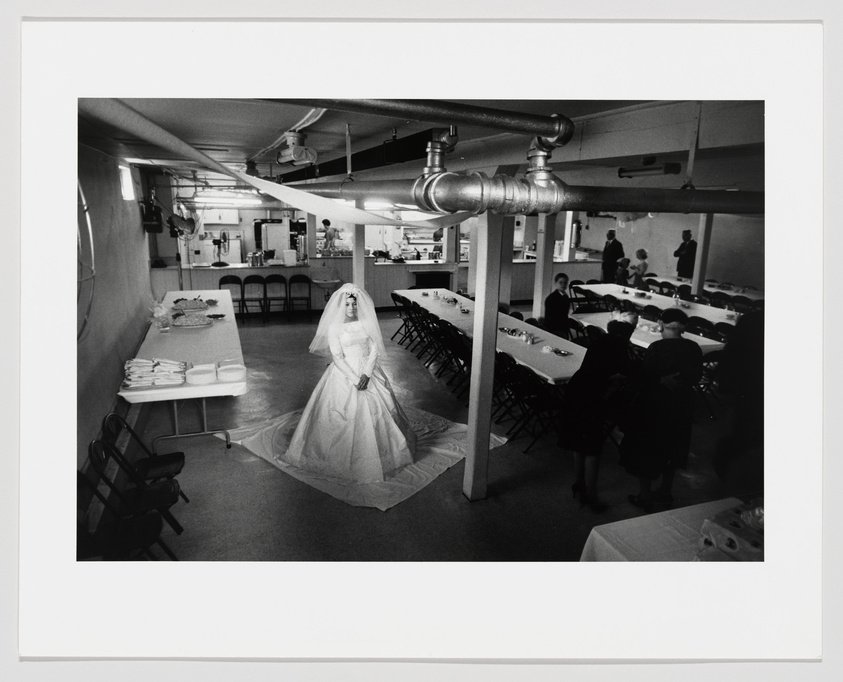

Bride in the Cellar, Graniteville, Ill. 1965 –

In a spacious basement, a bride in a flowing white gown waits thoughtfully beneath exposed pipes and empty tables, anticipating the start of her wedding reception.

In his last book, “Departures and Arrivals” (2012), he reflected, “The kinds of stories I chose to tell were mostly about American myths. I photographed small towns, immigrants, the barrio in New York, and the significant changes that occurred in the 1960s. I aimed to be both a witness and to express my feelings about all of this. However, I began to question whether there was a limit to my ability to serve as a witness. In the early 1970s, I started to doubt the authenticity of what I was observing because public events had become so manipulated and distorted. I found that I was more interested in capturing a pair of pajamas on a bed one morning in Brooklyn or a woman in Dublin carrying her groceries than in the grand machinations of politics and history as a whole.”

"Departures and Arrivals" marks his third monograph, offering a thoughtful collection of black-and-white photographs that portray ordinary moments within extraordinary historical contexts and more straightforward scenes of urban life. This volume serves as a significant reflection on his impressive fifty-year journey in American photography. Harbutt, in his introduction, eloquently expresses, “There are pictures of men and boys, women and girls, statues, and pensive monkeys—moments that have captivated me, evoked fear, and sparked joy.” He further emphasises, “History belongs to all of us, not just kings and generals,” reminding us of the shared human experience that his work celebrates.

Harbutt’s favourite photo, "Mr. X-Ray Man,” has an interesting story. He took it through a car window on Rue du Départ, right by the Montparnasse train station in Paris. You can spot bits of the city and even see a reflection of himself in the glass! What makes this shot so special is that it was completely unexpected, as he shared in his work “Arrivals and Departures.” He summed it up perfectly when he said, “What I like best is that no matter how the picture is made, it’s always a delightful surprise to see it develop!”

Today, many photographers strive to create images like this, but there’s often a lack of surprise in the digital medium. Personally, I seek out reflections in my work, and sometimes I end up pleasantly surprised. I avoid checking my shots or taking multiple images, as I prefer to approach photography like an analogue photographer. This unpredictability can lead to moments of magic in photography.

Mr. X-Ray Man

one of his last images: Self

Harbutt experimented with surreal composition and the juxtaposition of everyday forms in a style he described as personal documentary, which he facetiously branded “superbanalisms.”

I believe this interview has valuable insights, and I encourage you to take the time to read it. It could greatly enhance your understanding. It struck me how the assonance resonated with my sense of magic.

“One girl actually broke into tears when I told her that there are no rules. Different times. Photography is not a religion; it's not accounting; it's not based on logic only. There are no commandments and only a few would-be popes. This freedom is very seductive.”

Untitled, 1976

Single B&W photo of a mysterious situation, with a man in briefs lying facedown on the floor, with 2 men attending him and another 2 who appear to be lookouts. Stamoed Magnum Photos 1970.

Three Men Waiting, Emergency Room, St. Vincent's, NYC, 1961.