SAHRAWIS: 50 Years of Exile in the Desert by Pepe Alvarez-Rogel

(A journey into the Dakhla refugee camp. Part 2)

November 1975. The Green March - November 2025. The Great Shame

In November 1975, Francisco Franco, the dictator who had ruled Spain since the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939, was dying. Spain, which had colonised Western Sahara (a territory of about 280,000 km² in northwest Africa) in the early 20th century, handed over the administration of the region to Morocco and Mauritania. This occurred after the so-called "Green March," organised by Morocco, which began on November 7, 1975.

In 1960, the United Nations recognised that Western Sahara, as a non-self-governing territory, had the right to become an independent country upon decolonisation. The International Court of Justice affirmed in October 1975 that Western Sahara had not historically formed part of Morocco and confirmed the Sahrawi people’s right to self-determination. However, Morocco and Mauritania had different plans. In secret negotiations with Spain, the three agreed that Spain would retain fishing rights and access to most of the territory’s phosphate resources. At the same time, Morocco and Mauritania would divide the land.

On November 7, 1975, King Hassan II ordered around 350,000 unarmed Moroccan civilians and camouflaged soldiers among them, to cross into the territory from the north — the event known as the Green March. The Spanish army did nothing to stop it, and although the international community condemned the incursion (United Nations Security Council Resolution 380), Morocco effectively took control of the northern part of the territory, while Mauritania invaded from the south.

Many Sahrawis fled their cities to escape Moroccan repression and took refuge in the desert of Western Sahara, their own land. Human rights organisations and survivor testimonies report that around 3,000 Sahrawis were killed in bombings carried out with napalm and white phosphorus on Sahrawi territory. As the attacks intensified, survivors escaped eastward, crossing the border into Algeria, where they eventually established five refugee camps (known as wilayas) near the city of Tindouf (El Aaiún, Aousserd, Smara, Boujdour, and Dakhla).

The Polisario Front, the Sahrawi national liberation movement, declared war against Morocco and Mauritania in an attempt to expel them. But when Mauritania withdrew from the southern part of the territory in 1979, Morocco extended its control over the entire region.

In 1991, UN Security Council Resolution 690 established the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO), with the explicit mandate to organise a referendum on self-determination. However, more than forty UN resolutions reaffirming the Sahrawi right to self-determination have been ignored or sidelined, and the referendum has never taken place.

Outrageously, on October 31, 2025, the UN Security Council endorsed a proposal to make Western Sahara an autonomous region within Morocco. If this becomes definitive, the Sahrawi people will never have the independent country that is rightfully theirs. Once again, justice has been absent, and the economic and geopolitical interests of the powerful — especially those of the United States — have prevailed. Once again, a great shame for the so-called “civilised world.”

Today, around 176,000 Sahrawis still live in refugee camps in the Algerian desert, surviving in one of the harshest climates on Earth.

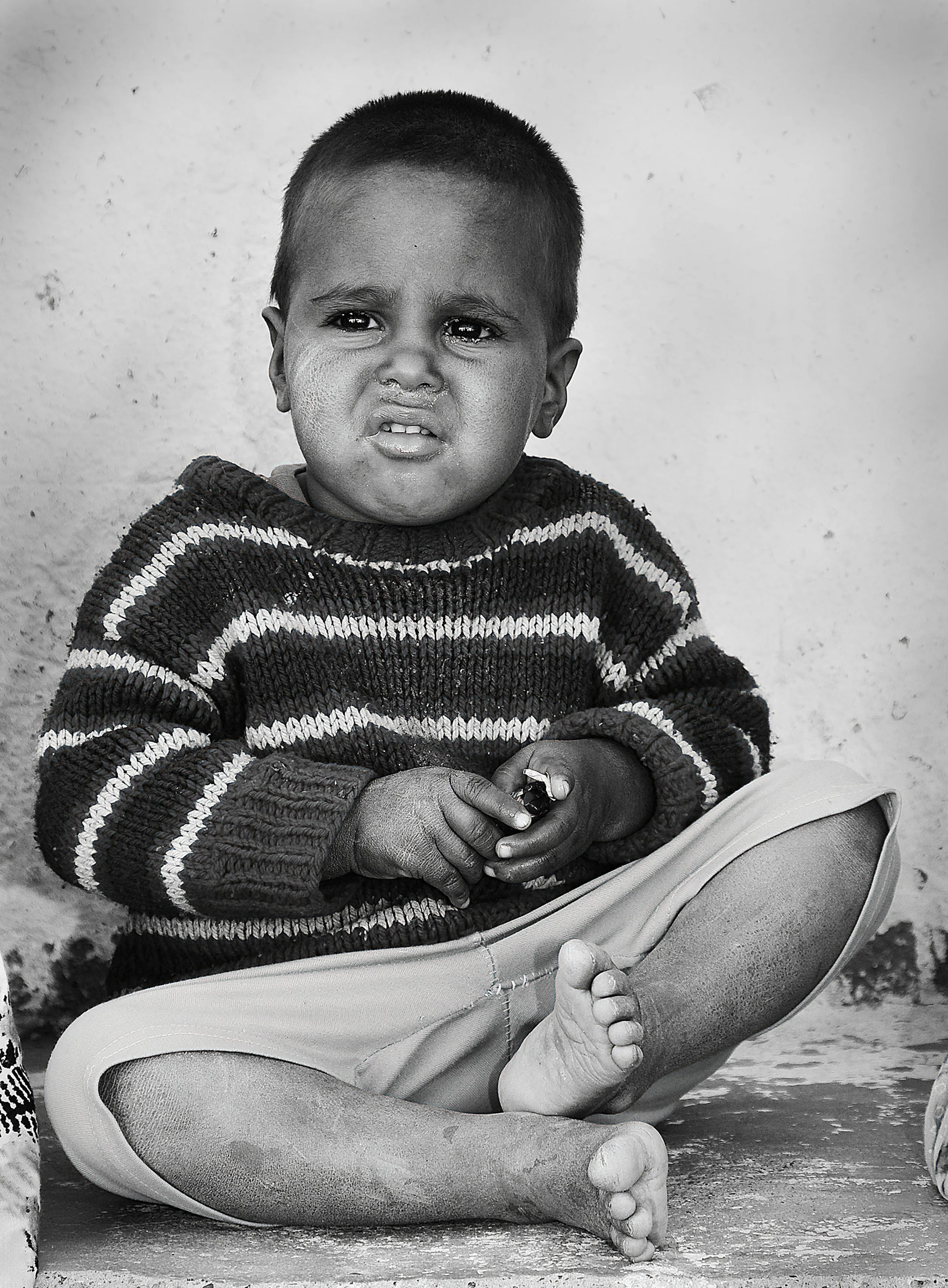

I took these photographs in December 2008 during my visit to the Sahrawi refugee camp in Dakhla, collaborating with an NGO from Murcia that sponsors Sahrawi children. In the eyes of the men and women I met, I saw dignity and pride — the pride of a people who know their land is theirs — but also exhaustion and disappointment, the result of an injustice prolonged for decades. The children, however, played joyfully with what little they had. If you gave them just the slightest chance, they would smile freely at the camera, despite their vulnerability. When I photographed them, I felt that I was documenting the future of a nation — that these boys and girls would soon become the adults leading an independent Sahara.

Seventeen years have passed. And now, when I look at these faces, I feel disappointed — and ashamed — to be part of this Europe, this “civilised” Western world, this society and this system driven not by justice or humanity, but by interests, power, and profit. I ask myself whether we deserve this planet at all, with all our greed, rivalries, cruelty, and ambition.

I offer these images as a tribute to the Sahrawi people. And I apologise for belonging to the “civilised world” — the world that has condemned them to live without the country that is rightfully theirs.

These photos were made possible thanks to the warmth and generosity of the Sahrawi men, women, and children of Dakhla camp. I am deeply grateful to all of them.