Letter from Seoul 42

Preface

My grandfather, Martin Kennedy, was a 10-year-old immigrant when he arrived at Ellis Island on June 29, 1906. The story of my Irish immigrant family is about the fates of common people everywhere. They were small actors in history, yet they were men and women with minds, wills and voices. And pride.

By retelling their stories, it becomes easier to understand the hardships endured by all people who dream of basic dignity for themselves, their families, and the generations that follow.

No immigrant deserves to be kidnapped off the streets by masked mercenaries, dispatched by a degenerate President who is the son of an illegal immigrant, who is married to an immigrant, who is a convicted felon, who tried to overthrow the government, who is a Russian asset, and who is both a serial grifter and a serial liar.

I wrote all this thirty years ago when I fully committed to documenting my family history as thoroughly as possible – especially while older family members were still alive (including my current age), and could fill in many blanks, not to mention still possessing letters and photographs from those earlier times. Both my father’s sister, Margaret (née Kennedy) Murphy, and his brother’s wife, Rose Kennedy, were invaluable sources of help. Those women are now in a better place. Jim Murphy, my cousin, was at our apartment one evening early last October with his wife, Akiko. She is Japanese, an immigrant – and probably a naturalised U.S. citizen. Jim and Akiko usually make two trips a year to Tokyo to visit her family. Jim and Akiko have lived in Los Angeles for forty years or more. Los Angeles is Ground Zero for Trump to establish a Police State.

Beginning in 1845, the Irish Potato Famine decimated the country, affecting people of all classes but especially the poor Catholic tenant farmers. People who depended on potatoes to survive suddenly had no food, and if they ate the other crops they faced evictions and a life of destitution, an even worse fate. Many of the poorest simply died.

Known by most scholars as An Gorta Mór - The Great Hunger, this catastrophe was the Irish Holocaust.

The scene at Skibbereen, west Cork, in 1847. From a series of illustrations by Cork artist James Mahony (1810–1879), commissioned by Illustrated London News 1847. “The first Sketch is taken on the road, at Cahera, of a famished boy and girl turning up the ground to seek for a potato to appease their hunger. ‘Not far from the spot where I made this sketch,’ says Mr. Mahoney, ‘and less than fifty perches from the high road, is another of the many sepulchres above ground, where six dead bodies had lain for twelve days, without the least chance of interment, owing to their being so far from the town.'”

SAVE ARTWORKFOLLOW ARTIST, Irish School, 19th Century, Irish Wrestles with Famine, 1890 Supplement from the United Ireland paper 1890

The harrowing memory of the starvation, disease, and destruction that engulfed Ireland during the Famine altered all relationships forever. It sent shockwaves throughout Irish society, and the Famine's horrific shadow left no one untouched.

By 1850 at least 1.5 million Irish had died and another 1.5 million had emigrated. No one can fully capture in words the magnitude or the intensity of the suffering and hardship endured by the Irish people.

This tragedy is particularly appalling because there was no true famine. The Irish died of hunger in the midst of abundance which their own hands created. There was plenty of grain, beef, butter and milk, but it was all destined for Great Britain, the most powerful and wealthy empire the world had ever known.

The Irish Holocaust is not something for us to forget. Famine is a useful word to avoid terms like genocide and extermination. Yet the disaster in Ireland was a starvation based on systematic government policy. The English administration of Ireland during the famine was a terrible crime against the human race.

The Great Famine condemned the Irish to be the first boat people of modern Europe. During the second-half of the 19th century, in every corner of Ireland, there were families who had voluntarily separated, sure of nothing except they would never see one another again. Those who left prospered or not, according to God's plan and fate's whim. Those who stayed behind were gradually forgotten, their passing unremarked. The only witness was the mute testimony of the stones in the fields.

Not all of us can understand the nature of an immigrant’s privations, but we can take the opportunity to pay tribute to the memory of those who struggled for a decent life, and the courage of those who survived. May their ghosts know we still care.

Part I

My grandfather, Martin Kennedy, was born on December 25, 1895. Two years later, his mother died giving birth to his sister, Ellen. By early April, 1900 my great-grandfather, John Kennedy, left Ireland for good and joined his three younger sisters who had already immigrated to Kerry Patch in St. Louis - so named for the number of Irish immigrants from County Kerry.

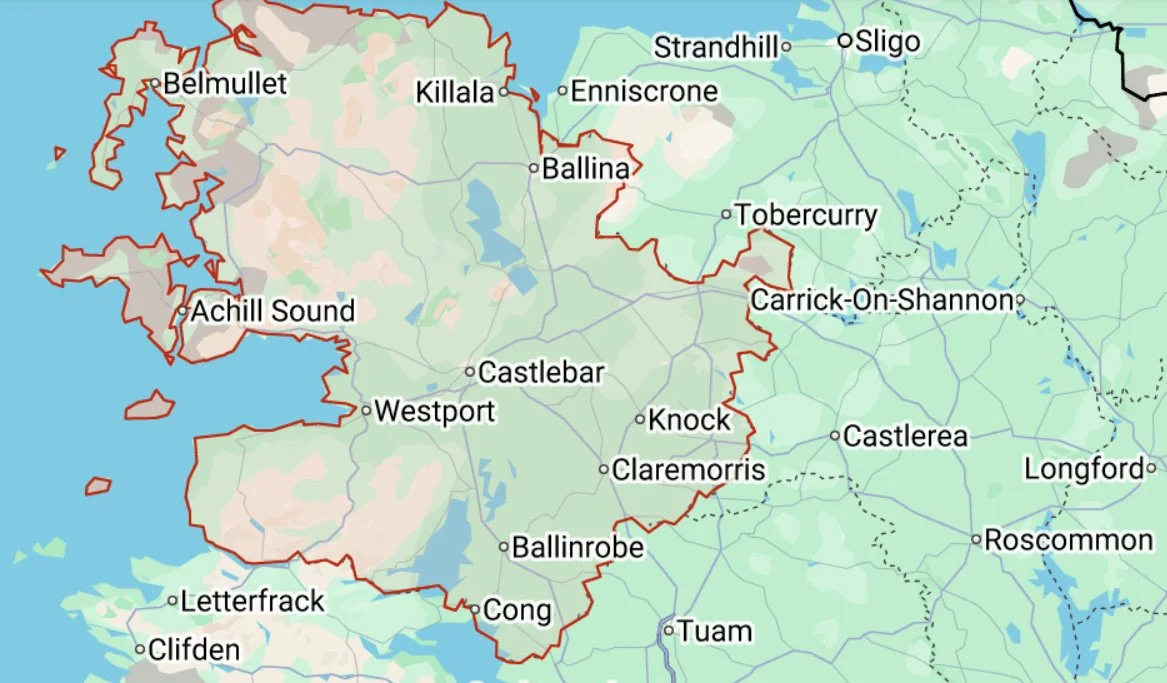

My great-grandfather left his son and daughter in the longtime family village of Balla, near Castlebar in County Mayo. At first, the two young Kennedys lived with Thomas and Margaret Higgins, one of their father’s older sisters and her husband. Later, they joined the Patrick and Mary Roche household, their mother’s brother and his wife.

County Mayo

The Great Famine was particularly tough on the young, unmarried women because the centuries-old dowry system collapsed overnight. It was customary for the father of the bride to provide the groom’s family a cow or a small section of land for “taking” his daughter into the family.

Now the girls had to find work in foreign lands, and send money back home. Most of the Irish exodus was straight to America, because the British were so thoroughly hated in those years. This was known as the American Wake, because the parents knew they would never see their daughters again, yet they desperately needed financial assistance back in Ireland.

Delia Higgins was John Kennedy’s niece. Five years after he immigrated to St. Louis, she visited him and other relatives. By this time, John Kennedy had been working as a ticket collector for the street car company, married Kate Kelly, an Irish widow and bought a house at 2519 North Spring Avenue.

John Kennedy’s dreams of hope inspired his family in the Old Country, and others soon followed in the Chain Link of Immigration to St. Louis.