Letters from Seoul 41

Tails of St. Louis

Our Lady of Dogtown

Hail, many, fell of greats, the Lord is with thee, blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus.

Holy Mary Anyhow, Mother of God, pray for us sinn finners, now, and in the hour of our death.

We pray to St. Vincent de Paul, St. Martin of Tours, St. Anonymous, St. Eponymous, St. Pseudonymous, St. Homonymous, St. Synonymous, St. James of Compostella.

Amen.

Weeks before my tenth birthday, I left the St. Louis suburbs of upward mobility, and returned to the traditional middle-class Irish-Catholic neighborhood of Dogtown, where my life began in 1951. My mother had decided that my father was a horse who wasn’t going to finish the race. She gave him his walking papers, and they were divorced six months later.

On Friday, I was sitting in a brand-new suburban school that reflected the American Dream of prosperity, a new house, a new car and neighbors with growing families. On Monday, I was sitting in an old two-story school building from 1917, named for Admiral George Dewey, the first man in U.S. history to attain that supreme rank. He is best known as the hero of the Battle of Manila Bay during the Spanish-American War. The decisive battle occurred on May 1, 1898.

By 1961, no one cared about Admiral George Dewey, and the namesake school was a drab affair with creaky wooden floors, old teachers and old books. The students who populated the school cafeteria were reminiscent of the Dead End Kids in Angels with Dirty Faces (1938) with Cagney and Bogart. Sinatra knew the score and I had been riding high in April, now shot down in May.

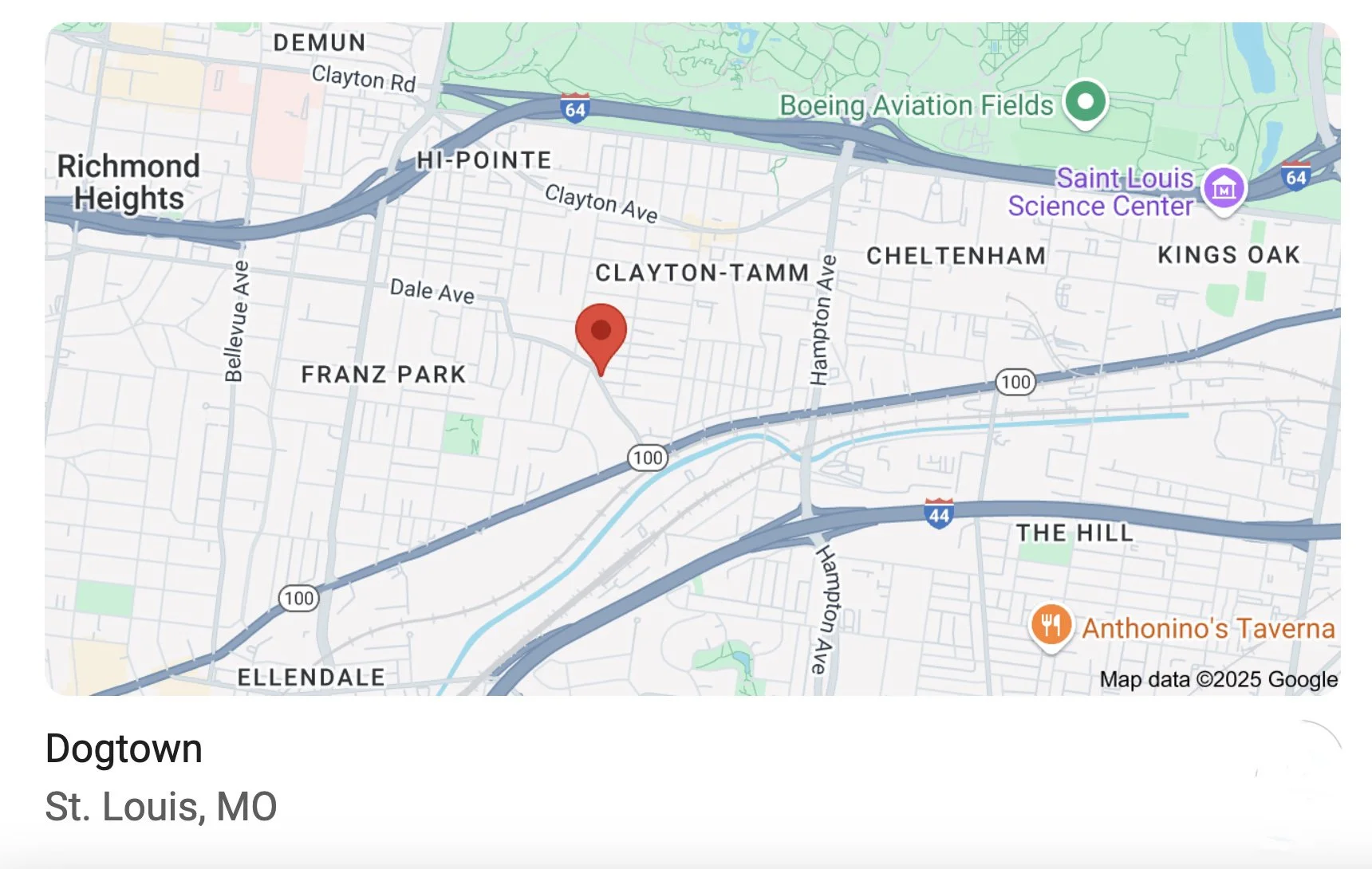

And so I was back in Dogtown, that brick and mortar neighborhood immediately south of Forest Park in St. Louis.

The expansive park was the St. Louis version of Central Park in Manhattan. It was the site of the 1904 World’s Fair. In that bygone era, St. Louis was the third largest city in America – with Manhattan and Brooklyn holding the first and second spots. The 1904 World’s Fair was a turning point for American food, since the public was introduced to the hamburger, the hot dog, the ice cream cone and iced tea.

The origin of Dogtown’s name has an interesting history, yet one that seems most likely is the 1904 link to the Philippine Exhibition, because the Filipinos required a steady supply of dogs for their culinary habits. So, St. Louis dogcatchers simply scoured the neighborhood immediately south of Forest Park to round up stray canines for the Filipinos. To this day, the neighborhood is still known as Dogtown, which includes Clayton-Tamm, Franz Park, Hi-Pointe, Cheltenham, Ellendale and Kings Oak.

(* The term "Dogtown" was commonly used in the 1800s by miners to refer to clusters of small shelters around mines. The earliest known reference appears in an August 14, 1889, article in the Missouri Republican, which describes a lost five-year-old boy living in "the classic precincts of Dogtown, near Cheltenham.")

During all my student days, the narrative about the Philippines and the Spanish-American War is that the Filipino people welcomed the Americans as liberators.

The Spanish Empire followed the same trajectory as all such political constructs, the basic cycle of any life. It’s only with the passage of time that one can recognize how the beginning, middle and decline unfolded.

For the Spanish, the end accelerated when Napoleon Bonaparte installed his older brother, Joseph, as the monarch of Spain in 1808. When the colonial master is run out of town, then let freedom ring.

It took a combined force of six European armies to defeat Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815. The Corsican’s greatest strength was abstract reasoning. He was nothing less than a Grand Chess Master, yet after 20-years of victories on the battlefields of Europe (omitting the disastrous Russian campaign of 1812), he had shown all his moves. Napoleon might have prevailed once more in 1815, but the array of six armies decimated his horses.

It could well have been Napoleon who said what Shakespeare attributed to Richard III (sometimes called Richard the Turd by Aussies), as he lost the crown at Bosworth Field on August 22, 1485 near the Scottish border: “My kingdom for a horse.”

By 1821, Napoleon had died at St. Helena, that lonesome rock of an island in the South Atlantic Ocean, and there was no chance of a resurrection and roaming about for 40 days, like the Jewish zombie.

So, all of the Spanish colonies in Latin America revolted in 1821 and established their independence. That was the end for the Spanish, except for Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam.

For decades, the Southern slave-owning oligarchs of America had designs on Cuba. Yet nothing came of this agenda until the Gilded Age of the Robber Barons in the late 19th century.

A prism for understanding American history is how the country evolved through a series of land grabs. To go from sea-to-shining sea, Manifest Destiny – the concept of Romantic Nationalism first expressed by New York City journalist John Louis O’Sullivan (1813-1895), was used to justify the annexation of both Texas and the Oregon Territory in 1845.

This was quickly followed by a phony war with Mexico (1846-1848) that resulted in total defeat for our neighbor to the south – known officially as Estados Unidos Mexicanos. The victorious Americans decided to only annex half of Mexico.

And then after Sanford Dole engineered the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893 for the sake of more land for his pineapple plantations, Manifest Destiny was invoked again to justify another land grab. Besides, Pearl Harbor was quite valuable as a stepping stone to the markets in China.

But Guam and the Philippines were even closer to China. Besides, Japan had said good-bye to the Shogun era and roared out of nowhere toward becoming an imperial power and had overthrown the government of Okinawa in 1890.

By the time I had my first formal U.S. history class as a high school junior in the late 1960s, the standard narrative about Admiral George Dewey and his victory over the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay was that the Filipinos welcomed the “American liberators,” and wanted to be part of the United States.

File that narrative under Lies My Teachers Told Me. See James Loewen’s book of the same name.

Yet it is a mistake to automatically regard the omission of facts in a historical narrative as The Big Lie. Inconvenient truths are frequently sidestepped or ignored for lack of time. At the high school level, it’s impossible to adequately cover a nation’s history in a one-year survey course, even for a country as young as America – especially on a block schedule.

During 1812, while Napoleon was bogged down in his Russian fiasco, the British military returned to America and eventually burned the White House on August 24, 1814.

The United States surrendered and the Treaty of Ghent (Belgium) was signed on December 24, 1814. The British were not interested in re-establishing any control over the Americans – considered “too unruly” to bother with. The British simply wanted to make the point of fuck you; that’s why.

Because communication abilities were exceedingly slow in those days, Andrew Jackson’s decisive victory over the British in the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815 occurred after the Ghent Peace Treaty two weeks earlier.

“Sorry about killing you lads,” General Andrew Jackson said. “Why don’t you pick yourselves up, and go home to your families. Mistakes happen.”

The War of 1812 isn’t even part of a U.S. history textbook any more. It’s not convenient.

In most ways, high school is no different from the cafeteria experience. Teachers place a small slice of geometry, Victorian literature, and the Civil War on a student’s tray to sample. Go ahead and try some. If this is appealing, study the subject more thoroughly in college – or on your own.

The book to read for an awakening about American history is Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States. Zinn makes no pretense about objectivity. History is the record of the victors. Zinn devotes his attention to the forgotten voices of those sidelined or overlooked by history. Many AP U.S. History classes have a class set of “the Zinn book” to accompany the safe, white-washed version of American history that is peddled by textbook publishers and school districts everywhere.

This is how one learns that the Filipinos were not interested in a new overlord after Dewey’s victory in the Battle of Manila. So, when it was clear the Americans were like the police one calls to settle a dispute with a troublesome neighbor, but stay for dinner; then take over the TV remote control; take over the refrigerator; take over the master bedroom and just won’t fucking leave, you have the three-year Philippine-American War (1899-1902).

To suppress the Filipinos in their efforts to achieve true independence, the Americans put many of the men in concentration camps. This inhumane practice was inspired by the Spanish who did the same to unruly Cubans at the outset of the Spanish-American War. The Nazi Germans were not the first to use this tactic to break a person’s spirit.

The American justification for its first imperial war was to subjugate the Filipinos to educate our “Little Brown Brothers,” a derogatory term coined by William Taft, the first American Governor-General of the Philippines, who later became the U.S. President from 1909-1913.

Taft was later appointed as a Supreme Court Justice.

Taft was also such a fat fuck that he got stuck in the bathtub of the White House, and had an indoor swimming pool built so he had “room to move.”

And, of course, another leading justification for taking control of the Philippines was to Christianize the Filipinos. The fact that Filipinos had been Catholic for centuries was not good enough. The true American was ... White, Anglo-Saxon Protestant. And, if you were not of the Caucasian Persuasion, you could be Protestant. Anything but a damn Catholic, and their pagan saints.

By the way, I was baptized at St. James the Greater Church in Dogtown on January 26, 1952. I consider myself a recovering Catholic.

During the Philippine-American War, a large number of Americans were opposed to the conflict. Mark Twain was one of the most outspoken critics of the war.

As a quick aside, both Mark Twain and Leo Tolstoy died in 1910. The Nobel Prize for Literature was first awarded in 1901 – yet neither of these writers made the grade. What the absolute fuck?

The U.S. viewed the Philippine-American War as an insurrection, and not a legitimate war.

Regardless, the U.S. officially proclaimed the conflict over on July 4, 1902. However, sporadic fighting continued for several years.

As a result of the Land of the Free and Home of the Brave taking control of the Philippines, there were about 4,200 American casualties and over 20,000 Filipino combatants who died. As many as 200,000 Filipino civilians died from violence, famine, and disease.

Two years later, when men roamed Dogtown in search of stray canines for the Filipino Exhibition at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, the past started to recede from memory.

Yet as William Faulkner reminds us: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

American Progress (John Gast painting)

Battle of Manila Bay by James Gale Tyler (1898)