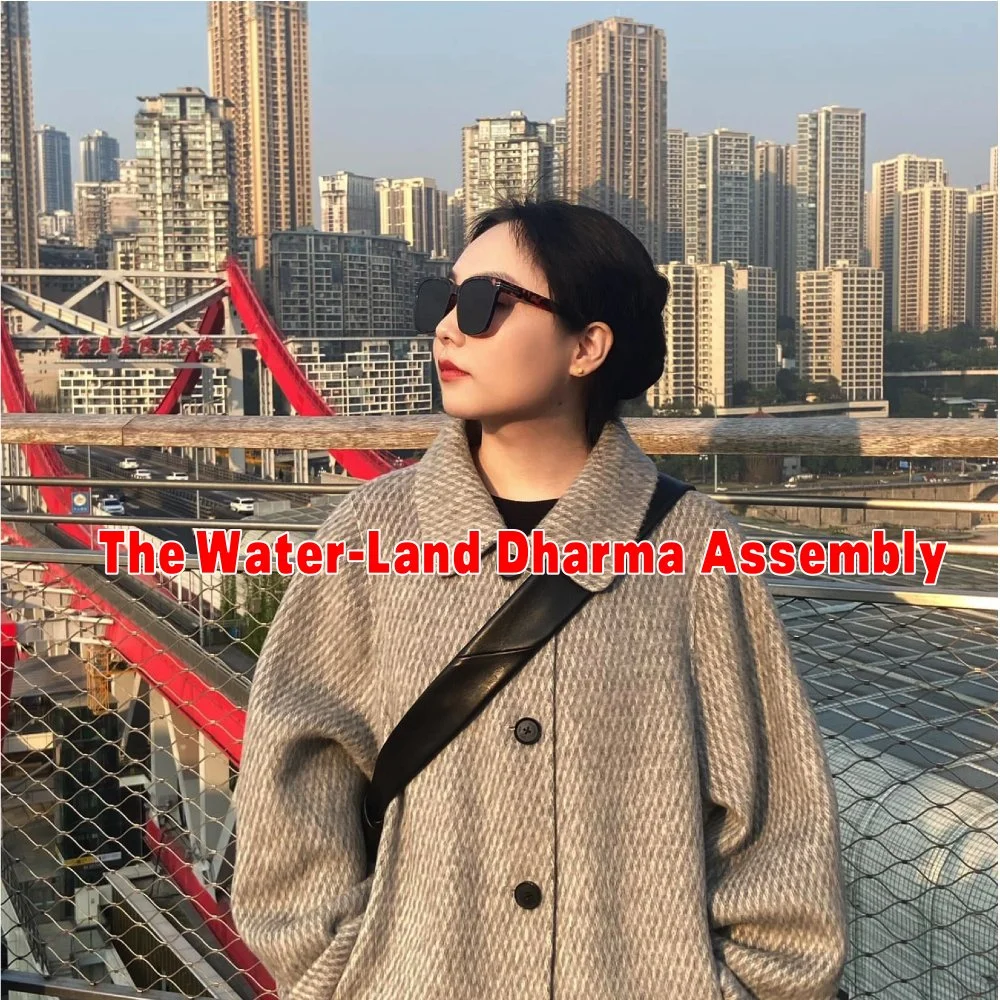

My City: A Chongqing Story

A Touch of Green

These buildings have stood long before I was born. The crimson slogans on their walls have paled, yet the ivy grows thicker with every passing year. Some have slumped into ruins, their fractured bricks sprouting defiant dandelions; others tilt wearily, their windowsills still draped with sun-bleached laundry. Only a few remain inhabited, their doorways guarded by sleek electric scooters.

Wild taro has colonised this derelict room. No one noticed when it first took root.

The ceiling is in ruins; cracks vein the concrete floor. A stray breeze, perhaps, carried in the seed. It forced its way through a fissure, thrust out a head, and anchored itself.

Rainwater drips through the holes. And the leaf, unhurried, unfurls. A stubborn green, glowing defiantly within this derelict factory building.

Villagers say this factory once processed scrap guns and cannons. During the War of Resistance Against Japan, the valley sky was often crimson with fire, the very ground trembling beneath. The acrid tang of gunpowder mixed with the smell of damp earth, catching in the throat. Under dim yellow lights, figures hunched over, their hands cold on chunks of iron. Clenched tight, repaired—these became the life-saving hope of thousands of households.

Later, it housed railway workers. And then, it stood empty. Stacks of firewood turned it into a shelter for stray cats and dogs escaping the rain.

Beyond the back door, on the tracks, a clatter-clatter-clatter—an old train laboured past. Its carriages were fiercely rusted, shedding flakes like dandruff. That laboured, wheezing rumble… it sounded almost like… like the old lathes in this very factory, gasping for breath in years gone by.

A figure emerged from the tunnel mouth. A hoe rested on his shoulder, its handle polished smooth by sweat and time. He walked slowly. Each step deliberate—a farmer's soles forged, inch by inch, in the soil.

A man carrying a shoulder pole approached from the opposite direction. They passed. The hoe handle and the pole end brushed—just a slight brush.

"Mmh."

Their steps didn't pause. Each went his own way.

The factory bordered the Yangtze, its waters thick and yellow, flowing ceaselessly eastward day and night. To reach Songbao, one must first drift some forty or fifty kilometres downstream to Chaotianmen, then turn the boat around and chug twenty or thirty kilometres up the Jialing River.

Boats like this existed long ago. The place now called Songbao was once Dabao. In the 1930s, an American missionary journeyed upstream on the Jialing River just so that his boat could moor here. He saw densely wooded hills, serene and secluded. Captivated, he decided to establish a school.

The Nationalist government was still in power then. The missionary acquired land from a landlord surnamed Zhou and planted many pine saplings. Within a few years, a pine forest grew, and Dabao became Songbao. The missionary school flourished, enrolling two to three hundred students, mostly children from poor families.

A small church of blue bricks once stood atop the hill. Later demolished, it became a kindergarten. On the southern slope below the church, sixteen school buildings stood in a neat arc. All were orderly rectangles, uniform with blue-brick arched doors and windows, clean and crisp to the eye.

Today, it serves as the residential compound for families of the Geological Instruments Factory, and it is not slated for demolition yet. Downstairs, a woman's sharp, clear voice echoed in an empty room as she answered the phone: "My place is cheap, three hundred a room. Settle in first, move when your job's steady."

The pines are still the same, their resin scent unchanged. Only the people beneath them have changed, several generations now.

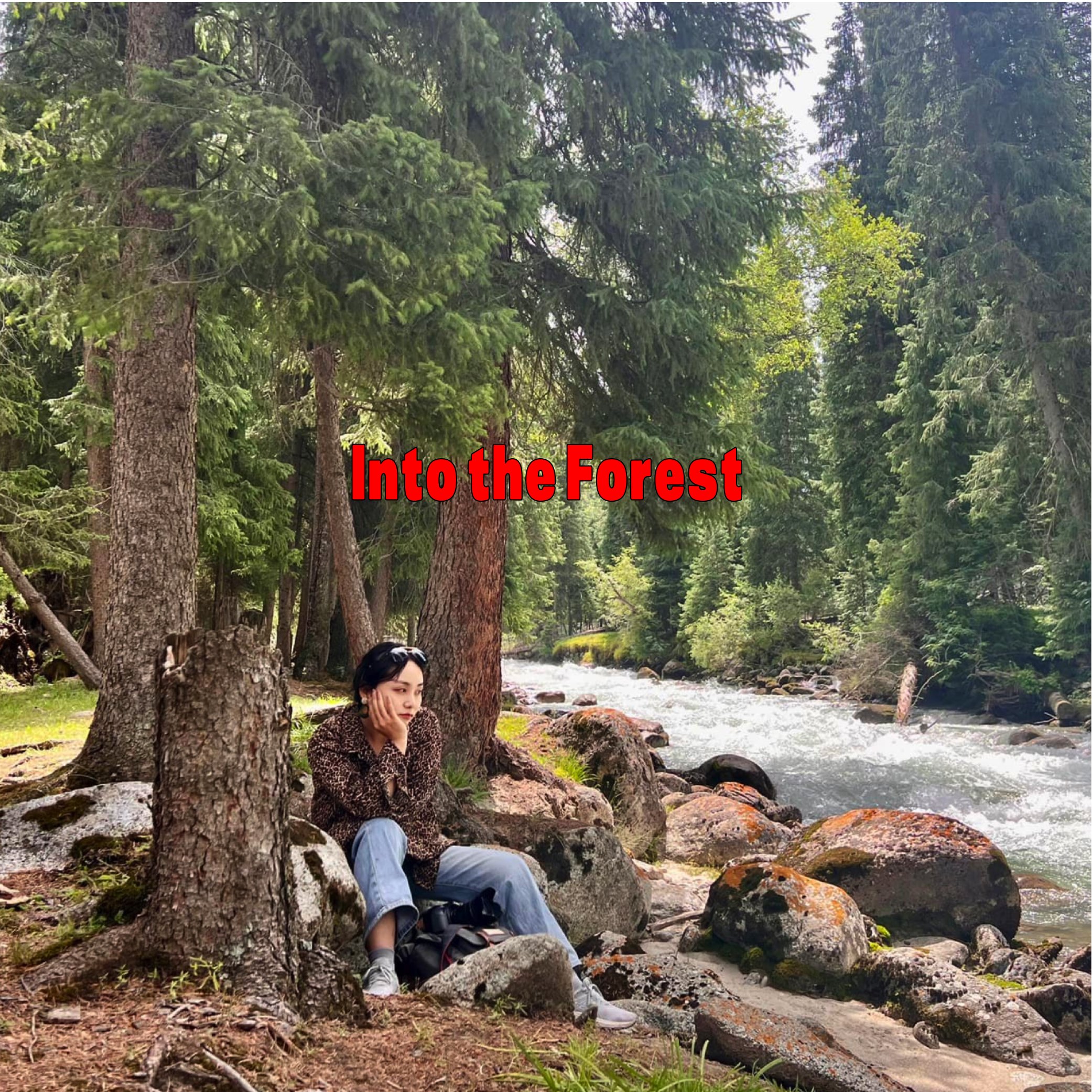

Twenty kilometres southwest of Songbao lies Chendian Village. At its entrance stands a centuries-old Ficus virens, its yellow-veined bark tougher than human flesh.

Chendian Village is empty.

Under the blazing sun, this vast village holds only this ancient Ficus virens, guarding a sprawl of squat, Stalinist neoclassical bungalows pressed flat against the earth. These single-storey, grey, dusty buildings, each with a square arched portico, were built in the fifties. The tree's shadow is dense, sprawling across the concrete like spilled ink, clutching the ground tightly. Wind whistles through the empty doorways and window holes of the deserted buildings, carrying away all former sounds —the barked commands of the artillery school, the clatter of Huxi Electric Machinery Factory, the echoes of a once-bustling time.

The tree lives freely. Limp from the day's sun, it gathers strength at night, roots drilling deeper into the earth. Where new walls meet the ground, bricks are forced apart by roots; earth swells silently, the surface buckling. Before long, those walls will collapse. Bricks tumble down. Moonlight, like water, spills through the breach, slowly soaking into the newly exposed roots. Thick and powerful, coated in damp earth, they look like arms reaching up from the depths.

The tree means no harm. It simply lives as it must, growing where it should. This low wall built by man cannot ultimately bar roots from seeking their destined place.

A few elderly villagers remain, refusing to leave, still dwelling in the tilting old buildings. They grow vegetables haphazardly outside their doors, tend a few pots of flowering plants. Bamboo chairs sit against the walls; people rock in them, fanning themselves, a cat curled at their feet. Life is quiet enough.

But news from outside still filters in. Talk of exchanging old square footage plus twenty square metres for a new apartment. Though smaller, the new place demands decoration fees, property fees, parking fees. Leaning on low doorframes, the elders listen and calculate –The bamboo chairs age—too weary to migrate.

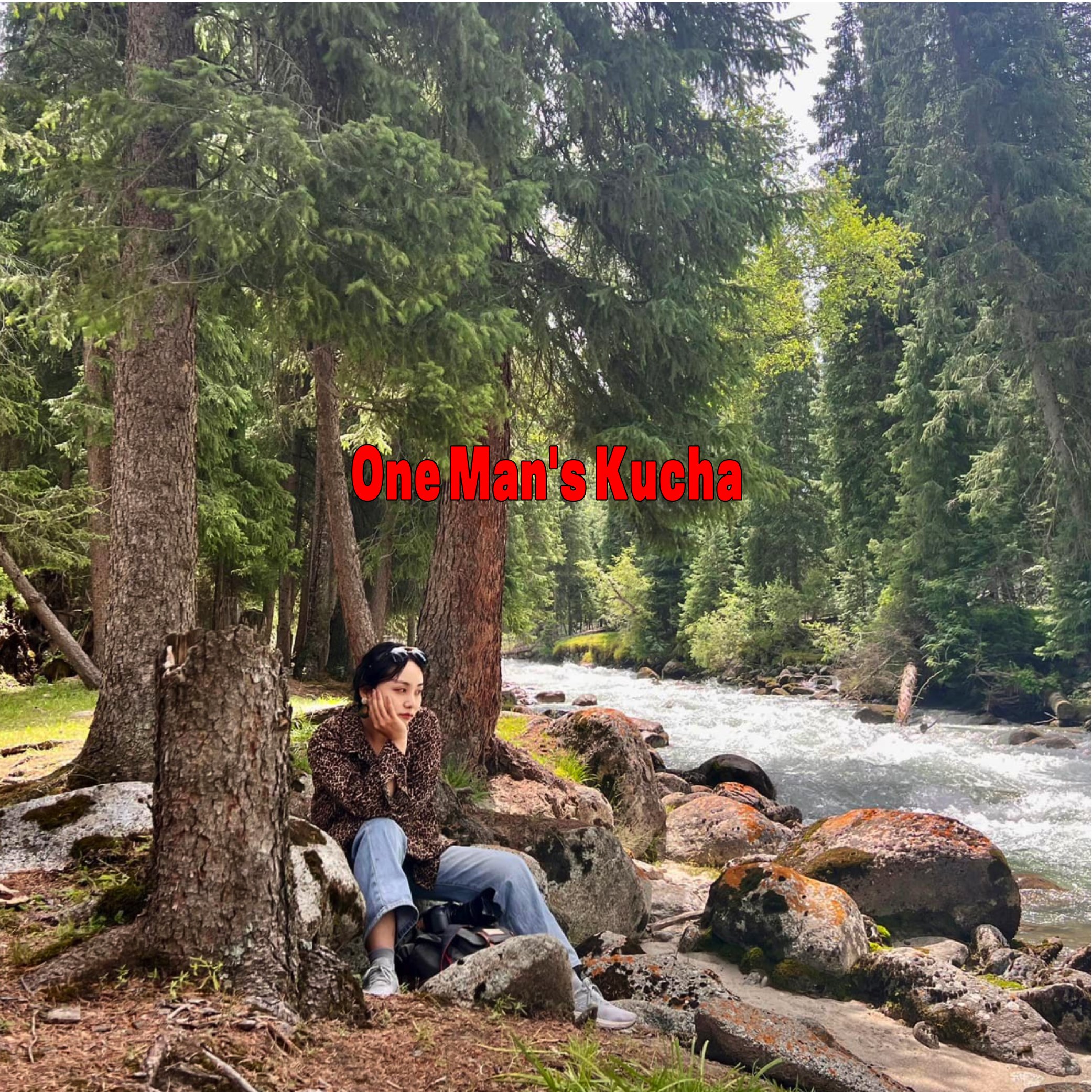

Twenty kilometres southwest of Chendian Village lies a residential area called "Kuaile Li" (Happy Lane). An old man is busy moving.

The name "Kuaile Li" doesn't sound local. In the sixties, when the Shanghai Prospecting Machinery Factory relocated here, workers brought their families and coined this name. "Li" (Lane) is the Shanghainese term for an alleyway, likely born of homesickness.

Kuaile Li boasts a three-storey, U-shaped red-brick building, once the office of the Geological Survey. The hall inside was cool. A speckled hen paced solemnly, eventually tiring and resting beside a glass counter laden with sodas, mineral water, peanuts, and sunflower seeds. A row of wooden chairs and stools lined the wall, polished smooth. Several mirrors of varying sizes hung on the walls—perhaps haircuts were offered here too. Old enamel kettles, chipped in places, sat on tables.

The wooden stairs groaned underfoot. On the landing, painted red and green, the colour scheme wasn't garish. Soviet in style on the outside, yet traditional Chinese in its interior palette—the architect must have been thoughtful.

Light filtered from the end of the second-floor corridor. Outside the window, a tree's leaves shimmered dazzling green.

Voices drifted up from below. A young man in uniform asked the old man, "This building's so old, sir. When will you move?"

"Soon, soon," the old man replied. "Most neighbours have already left."

The sound of furniture scraping came from upstairs. "Take another look—anything left to pack?" a middle-aged man asked.

"Nothing," the old man answered softly. "We've moved so much already."

The gate of the neighbouring factory was padlocked. Leaning against the wall was a large pane of glass, plastered with old photos: group shots, portraits. People in the photos wore Dacron shirts, smiling shyly. Two faded colour photos of children stood out most. Wedged in the top corner of the glass was a "Pujiang River Cruise" ticket, its stub bleached white as if the sun had licked it thin. At the glass's foot, a wild grass sprouted, a reckless green, its stem ramrod straight.

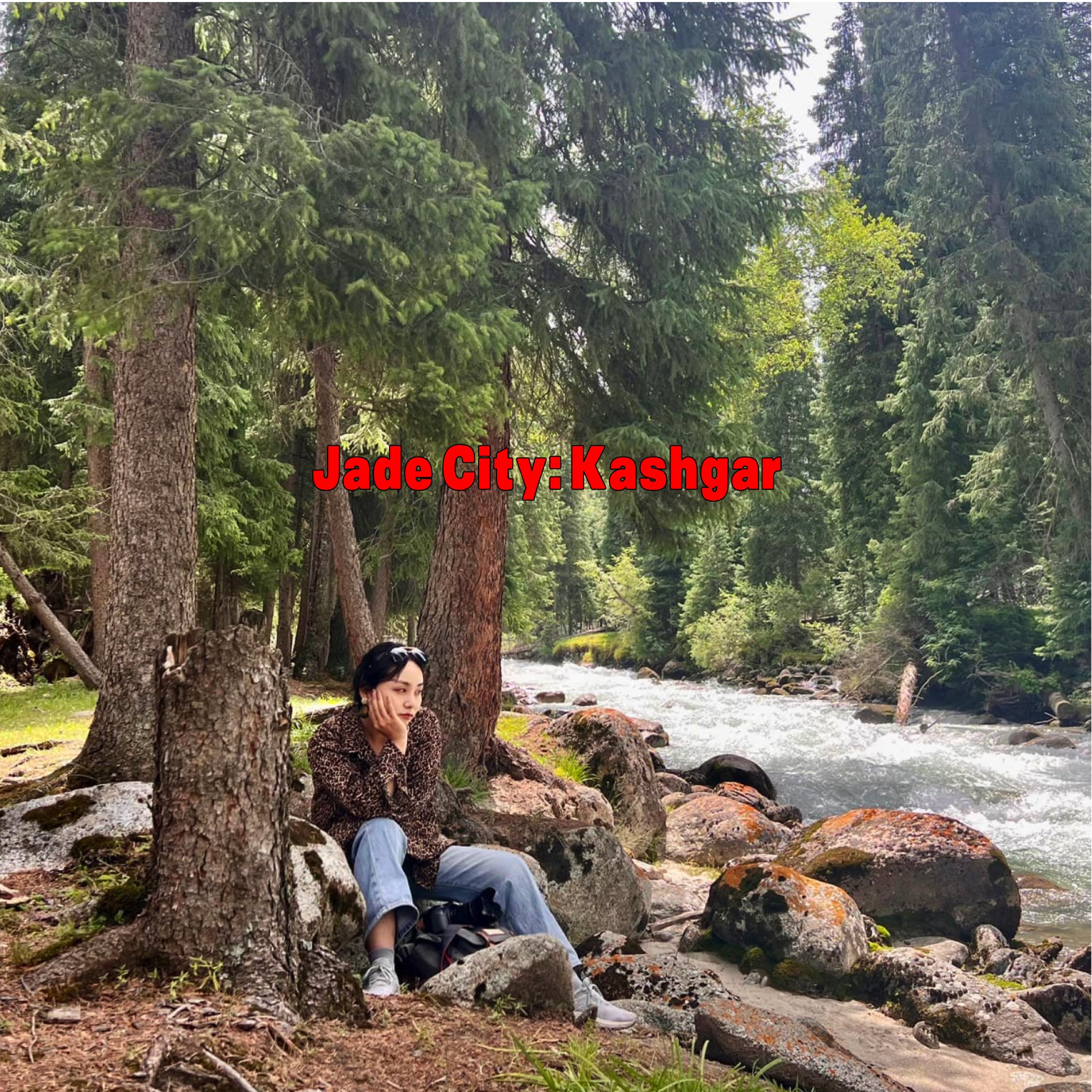

Beyond Kuaile Li, along the Jialing River, fifty kilometres upstream, a hilltop rises. There stands an old 1980s cinema, now just a shell. Plaster peels in large curls. Tattered remnants of the white screen flutter like streamers in the breeze.

Backstage, the red characters "No Smoking on Stage" still looked fresh. Beside them, on white paper, a performance schedule was neatly written in black ink, a long list of eighteen titles: "We Workers Have Power," "Ten Farewells to the Red Army," "My Motherland and I," "Chongqing Welcomes You"… The characters were clear, as if freshly penned yesterday. The concrete sink gaped toothlessly. The stairs were bare. Outside the window, a few green branches slanted, perfectly framing the grey-blue balcony of a distant building.

Light was better on the second floor. Sunlight streamed through high windows, pinning tree shadows to the floor. A landscape painting on the wall had faded, stained with watermarks. At the corridor's end, an empty window frame abruptly framed an old tree—its branches sparse, foliage luxuriantly green, a perfect, wild, natural bonsai.

The auditorium sank in gloom, the seats long vanished. Yet a few shafts of light squeezed in, pooling in a small, bright puddle on the empty stage centre. As the light shifted, one could almost hear the faint "click-clack" of an old projector, casting its familiar beam. But with no screen, the stories within that light had nowhere to land.

The clamour of the Third Front factories ceased in the early eighties. Like autumn leaves, they yellowed and drifted away. Now, the centrifuge factory atop this hill has also moved. The hilltop holds a few old buildings and this empty cinema. Some buildings have become nursing homes, mental hospitals.

The warm glow of sunset fell at my feet. Leaving the emptiness of Beibei hilltop, I began the journey back. The car descended alongside the Jialing River, its waters surging. Looking across the river towards the Yuzhong Peninsula, the silhouettes of buildings layered upon each other in the twilight, sinking into the river mist. As my gaze swept over that hazy expanse of prosperity, something stirred in a quiet corner of my heart—the image of the profoundly desolate old house at 178 Shengli Lu (Victory Road) surfaced clearly, like a shadow.

Its roof had collapsed at one corner, like an old man missing a tooth. The Ficus virens outside its window, however, was vigorous, its leaves glossy. This road was renamed in 1946, along with Kaixuan Lu (Triumph Road) and Heping Lu (Peace Road), to celebrate the victory in the War of Resistance. The small building, dating back to the fifties, was constructed from brick and wood, featuring a broad staircase and large windows. Though weathered, it retained a certain dignity.

Stories swirled about the building. Some said it housed the Southwest Bureau Public Security Office; others claimed it was the residence of "intelligence personnel." The truth remained unclear. The wood was badly rotten; footsteps elicited groans. The heavy smell of mildew made one want to retreat.

Just then, the slanting rays of the setting sun suddenly flooded through the west window. The cracks in the wall deepened, like wrinkles on an old face; the staircase railing, lit by the sunset, faintly revealed the grain of its vanished varnish. For a fleeting moment, it seemed voices echoed, footsteps sounded, papers rustled, teacups clinked gently—a sudden surge of noise and life, as if piercing through the thick wall of time, yet ethereal as smoke, impossible to grasp. This sense of futile struggle, like an invisible thread, abruptly yanked me away from this little building, hurling me towards another corner similarly abandoned by its era—the abandoned railway signalman's hut in the valley.

Most of the white tiles on the wall had peeled away. A slogan, "Serve the People, Battle Valiantly," its red paint faded to a dusty lilac, still clung stubbornly to the plaster. Inside, dry branches lay scattered, awaiting the day they'd be burned. Doors and windows were long gone, leaving only empty frames gaping.

I turned. And there, framed by a window hole in the wild grass, a few saplings had taken root in the soil, straining upwards with all their might. Their leaves were a vivid green. Silent, yet determined, they simply grew.