My City: A Chongqing Story

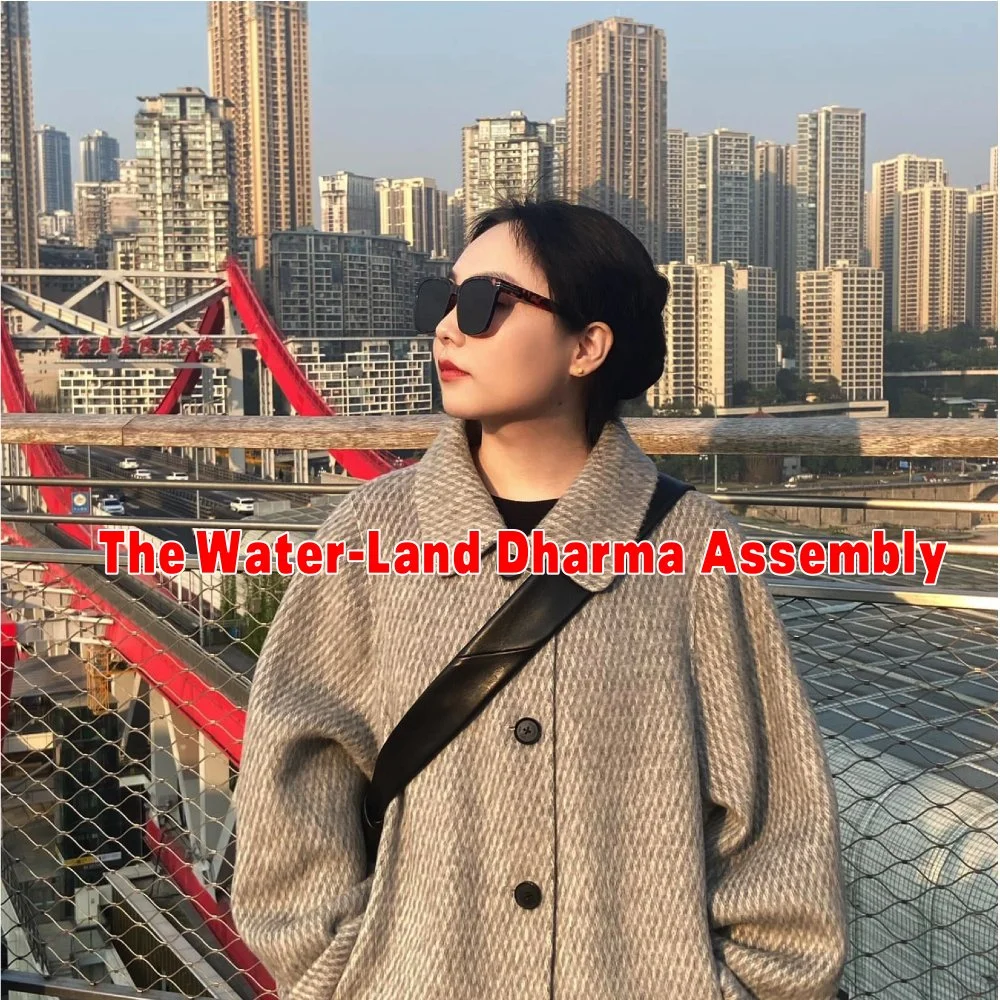

The Water-Land Dharma Assembly

On a lightly overcast day, I took the subway to Jiulongpo. Huayan Temple, nestled against the Zhongliang Mountain, had slopes that were not particularly high but lush with greenery. At the temple gate, several old Ficus virens trees stretched their gnarled roots across the stone walls, their sprawling branches casting a vast shade. The gate itself was rather imposing.

Passing through the gate and weaving around several halls, I sensed something unusual about the day. The air hung thicker with voices than usual, mingling with sandalwood and the hum of sutras, all charged with a quiet urgency. Volunteers in yellow vests hurried toward the Main Hall, arms laden with bundles of yellow prayer flags.

"What's the grand occasion at the temple?" I intercepted a monk dressed as a guest prefect.

The monk halted, pressed his palms together with a smile. "Amitabha. You've come at an auspicious hour, benefactor. Today the temple begins its Water-Land Dharma Assembly—seven days and nights of continuous rites."

A Water-Land Dharma Assembly! I had heard of it—the most magnificent Buddhist ritual, liberating all beings of water, land, and air, bestowing blessings and dispelling calamities for the living. No wonder the place was abuzz.

"Ah, what a fortunate coincidence," I said.

"Fortunate indeed!" The monk's smile deepened. "Do stay if you may. Such spectacles are rare." With that, he hurried off.

In the afternoon, bells and drums sounded in unison, their vibrations shaking the mountain woods. The Water-Land Dharma Assembly was now solemnly commenced.

Presiding Abbot Venerable Daojian held a willow branch, its young leaves a tender green. His golden-red kasaya glowed with particular luminosity under the gloomy sky. At the forefront walked two familiar monastic masters: Venerable Langyu of Bayue Temple in Tongliang and Venerable Langguang of Baisha Temple in Banan.

The willow branch dipped into purified water and flicked lightly, sending droplets scattering. Dark spots bloomed on the bluestone pavement, only to vanish moments later. The pillars and bronze bells glistened with moisture. Elderly women nudged their grandchildren forward, the little ones clasped their hands, though their eyes darted about curiously. One sturdy lad locked onto my camera lens, his "Amitabha" suspended mid-breath.

The scene took me back to childhood temple fairs with Grandma. While adults burned incense and kowtowed, I loved flipping through bodhisattva paintings. Some were exquisitely detailed, Guanyin's fingers so lifelike they seemed ready to pluck a willow branch; others were crude, the faces round as oversteamed buns. Grandma would chide, "Don't rummage; the bodhisattvas may scold." But I thought: if they're truly enlightened, why mind a child's play?

A nearby devotee explained, "This is 'sprinkling purification'—it's done with Great Compassion Water." I watched the damp spots on the bluestone fade. What exactly had been purified? No one could say.

Over the seven days of the assembly, I returned four times—sometimes staying only briefly, other times lingering for hours.

Huayan Temple was steeped in the sound of sutras. At first, it was just a monotonous drone, like a stirred-up hornet's nest. But as time passed, meaning emerged.

The Pure Land altar chanted "Namo Amitabha," one phrase after another, steady and unhurried. Dozens of voices merged into a soft, rustling harmony—like silkworms nibbling mulberry leaves—until the clutter in my mind began to settle.

The Lotus Sutra altar chanted the Wonderful Dharma Lotus Sutra, its lead monk's voice pure as a mountain stream—now rippling over stones, now plunging down ledges.

The Grand Altar was the busiest, with all ages bowing in the Liang Emperor's Jewelled Repentance—robes whispering, a white-bearded elder so devoted that his sweat dripped onto the prayer mat.

The Avatamsaka, Shurangama, and Ksitigarbha altars each had their own rhythms. Standing under the eaves, one heard "Thus I have heard" from one side and "Om mani padme hum" from the other, high and low, yet never discordant. At night, the chanting continued unabated. Cats dozed beneath the scripture tents, sleeping more soundly than the humans.

The Inner Altar held the deepest mystery. Through the windows flickered candlelight and monks in rainbow-hued ritual robes, their hushed voices weaving secrets. Now and then, petals would escape, gliding down the golden banners until one settled on my shoe-tip—a bodhisattva's blessing, though whose, I'd never know.

A young novice brought tea. "Chanting day and night—aren't you tired?" I asked.

He smiled. "When you chant, you forget about being tired."

As twilight fell, the Vajra Masters donned golden crowns and robes embroidered with intricate, colourful patterns that shimmered under the lamplight. Their chanting was unique, rising like tearing cloth, then falling like sighs. Their hands never stilled, shaping mudras—now like blooming flowers, now like grasping staffs.

The ritual master tossed offerings from a copper tray. Golden grains of rice scattered, and water droplets struck the bronze chime beside the altar, ringing softly. Incense smoke curled upward, swirling around the platform.

This was the "Flaming Mouth" ritual, feeding hungry ghosts. It was said their throats were narrow and their bellies vast, leaving them perpetually famished. The monks' chanting multiplied the offerings, filling them all. I mused that this was quite an economical solution.

Over the seven days, people came and went.

The lay devotees in their dark brown robes stood out the most. The robes, loose and dignified, lent them an air of solemnity. One white-bearded elder knelt straight-backed, lips moving incessantly, sweat pooling in the wrinkles of his forehead. A middle-aged woman bowed earnestly, though her gaze wandered—perhaps preoccupied with an ailing family member. A few young people lingered at the back, craning their necks, eyes darting everywhere.

The real workhorses were the volunteers in yellow vests—faded from washing, tossed over whatever they were wearing. The grannies running things greeted everyone with a smile: "Watch your step—don't trip on the threshold!" The young men stood like Weituo statues, silent and unmoving for hours on end.

A girl with braids tended the flower offerings. Each morning when fresh blooms arrived, she would carefully angle-cut each stem before coaxing them into perfect arrangements in crystal-clear water. Working with a celadon vase steadied in her left hand, she'd add the flowers two or three at a time with her right - pausing every so often to step back and assess the composition. One day I noticed a stray petal had landed on the tip of her nose, dancing there unnoticed as she worked.

Outside the main hall, a Tibetan lama sat on an old wooden bench, his maroon robes—faded yet still luminous against the dull grey wall. Eyes half-closed, he rolled the beads of his mala between thumb and forefinger, lips moving in near-silent prayer. When the last mantra faded, he rose with deliberate slowness, brushed nonexistent dust from his robes, and made for the bell tower. There, he pressed his phone into a tourist's hands, miming a recording gesture. As the tourist nodded, the lama hefted the mallet—clang—the bronze note hung in the air, trembling through the temple grounds long after the strike.

With such comings and goings, the assembly carried on in lively fashion.

On the final day, the skies cleared.

The hour of the Rite of Escorting the Sacred had come. The temple gates yawned wide as bells boomed, drums throbbed, cymbals clashed, and gongs resounded—fiercer and brighter than ever before. Dominating the scene was the Paper Ship to the Pure Land, a ten-foot-long marvel sheathed in gold and silver foil that glared under the sun. Upon its deck lay heaps of yellow scrolls: some to beckon celestials, some to soothe wandering spirits, and others inscribed with names yearning for deliverance—all jostling together in a vibrant crush.

Abbot Daojian led the monks in transferring the merit through chanting. His voice rolled like thunder as he invoked blessings: peace for the nation, liberation for the departed. Then the chorus of "Amitabha" swelled until even the leaves trembled on their stems.

The flame leapt up—the paper ship caught fire at once. The gold foil held its shape at first, but soon the edges curled, while the colored paper turned gradually to ash. The smoke rose straight upward without wavering.

All around, people tilted their heads back. A woman clutched prayer beads, tears falling silently as her lips moved in quiet murmurs. The fire burned more fiercely, the ship losing its form completely. The smoke thinned, fading at last to nothing.

The children, restless, had already run off. A few elderly women stayed, watching until the last wisp of smoke disappeared into the sky. Then they brushed their clothes and went their separate ways.

The Water-Land Dharma Assembly dissolved.

Devotees hurried to present offerings—red envelopes bright in the sunlight. The old monk tucked them into his sleeve without looking.

Monks from other temples shouldered their bags and walked out in small groups, whispering. The dark, bulging bags likely held sutras and ritual objects.

It was time for me to go.

Beneath the plaque inscribed "Sporting in the Human Realm" at the Amitabha Hall, a lone leaf spiralled to the ground.