My City: A Chongqing Story

Toward the Yangtze

Let's Go See the Flood

"Let's go see the flood!"

The shout, tinged with a local twang, struck like a match, igniting the entire alley. Weather-beaten wooden doors and gleaming security gates swung open one after another; even the chained dog wrenched against its leash. Streams of people spilt out from every side street, all converging toward the Yangtze River. In this mountain city cradled by two rivers, flood-watching wasn't just a spectacle; it was a ritual ingrained in the culture. The elders said that every Chongqing soul carried a few grams of Yangtze silt within; when the waters rose, those souls awoke.

From late June to mid-July, the river surged to 179.4 meters. On one side of the warning line, orange-vested workers stood with tense expressions; on the other, a carnival unfolded: women in pajamas snapped selfies while shirtless men plunged into the water. An old fisherman sat on a folding chair, his line taut as if locked in a tug-of-war with the river itself.

Near the shallows, the current gentled. A young man in red sneakers crouched to rinse his motorcycle, while children in sandals chased each other through the water. Women on picnic mats chatted about daily trivial matters, their eyes occasionally flickering toward a group of kids huddled around a phone—until a sudden surge of waves drew their gazes back to the river.

Further off on the grassy bank, a little girl swung her legs on a folding stool. Her father stood motionless by the water, watching the fishermen, his silhouette as still as a wooden stake driven into the mud.

A delivery rider in yellow leaned his motorcycle against the roadside, its engine still trembling. He propped himself over the handlebars, staring at the churning water beyond the railing. The murky current swallowed flakes of paint and rust, swirling them away as if they had always belonged there.

In Ciqikou, floodwaters had already breached the shop thresholds. The owners moved their goods with practised ease, as if performing a familiar rite. "An old friend," muttered a teahouse owner as he carried a mahjong table upstairs. Bamboo chairs bobbed gently on the water, almost like a deliberate decorative element. Neighbours in rain boots joked and snapped photos of floating plastic basins—to them, the flood was an annual visitor, troublesome yet oddly comforting.

Near Chaotianmen, car horns blared in a cacophony of noise. Vehicles lined up for miles, turning a half-hour drive into an hour-long ordeal. The scene was absurd: people rushing to see the river, only to be stuck on the way. When traffic ground to a halt, passengers spilt out, trekking through alleys and climbing fences like explorers—only to find an unfamiliar riverbank, the familiar landmarks devoured by the muddy torrent.

The Shanhuba Outside My Window

From my window, the river had swallowed the entire Shanhuba. Murky waves rolled over the sandbar, one after another.

In the dry season, Shanhuba was a different sight—a two-kilometre expanse of exposed sand stretching east to west, like a beached yellow-grey fish. In the 1940s, fighter planes took off here; by the 1980s, it had become a horseback-riding spot. Now, only reeds and generations of waterbirds remained. The river remembered everything, yet forgot everything.

A gap-toothed boy in green suddenly broke the calm, holding up a rock like a trophy. "Look! A dinosaur egg!" The old fishermen played along, feigning awe, though they'd seen this act yearly. One even pretended to trade his fish basket—inside, two scrawny crucian carp languished.

Tents dotted the grass like mushrooms after rain. Women fiddled with grills; men argued over tangled kite strings. An old man in neon green stood alone, his carp kite twitching in the wind. Nearby, a middle-aged man played the saxophone, sweating profusely, pausing whenever passersby neared.

Tripods lined up, lenses trained on the river. The photographers didn't care for the sunset; they waited for digital hearts on their screens. Tourists snapped selfies with the glittering Nanjimen Bridge in the background, its gold lights postcard-perfect yet surreal.

The new plastic walkway glared red, a wound stitched into the sandbar. A few old women insisted on walking the original mud path, their cloth shoes caked in last year's dirt. They tread carefully, as if stepping on something fragile.

When the Waters Recede

The riverbank after the flood held a peculiar exhaustion. Cargo ships dragged their wakes lazily; their horns wheezed like a sick old man's cough, struggling through the muggy air. Workers in straw hats scrubbed the amusement park's foam mats, the water sluicing away mud but not the stench of decay. The golden Buddha statue reappeared, its lacquer peeling, feet caked in dried sludge. Above it, in a stone niche, the water god Yang Si brandished an axe from his boat, glaring at the river—a guardian of vessels for centuries. Nearby, a faded football lay in the mud, its seams packed with yellow muck.

On a bench, a shirtless man slept deeply, one hand clutching a bulging backpack as if ready to flee. Behind him, a mural depicted distant hills, houses, a stone bridge, and a tiny boat—was it an old dock from decades past, or an artist's memory of home?

Across the river, a light rail train flashed by, its reflected sunlight stinging my eyes. Countless trees swayed in the water like a storyteller's tattered fan, on the verge of falling apart. Near a rusted freighter, an excavator gnawed at the debris, its metallic groans like those of a creature chewing on something indigestible.

"Dad, watch me!"

A girl in pink plunged into the river like a wave. Her father followed, steady as a ferry untying its ropes. His sunburned face reminded me of a temple guardian—same furrowed brows, same stubbornly set mouth. The orange lifebuoy around his waist flickered in the murk, resembling a deity's faded sash.

In the shade of the embankment, art students sketched. Sweat dripped from their temples, smudging pigments into odd shapes. They'd meant to paint the distant lighthouse, but it slumped on their canvases, as if melting in the heat.

The river receded, leaving driftwood strewn on the bank. The bark was scarred, as if the logs had endured horrors during their journey upstream. Someone might burn them, or the next flood might carry them away—who could say?

The old fisherman who came every year was no longer there. In his spot sat a young man in new sun-protective gear, gripping a cheap rod. Waves slapped at a freshly erected sign, its red characters shimmering underwater like urgent whispers. But once the water fully retreated, the words would blur, as if no one had ever bothered to read them.

Flood

After the flood

[Nights of Mountain City]

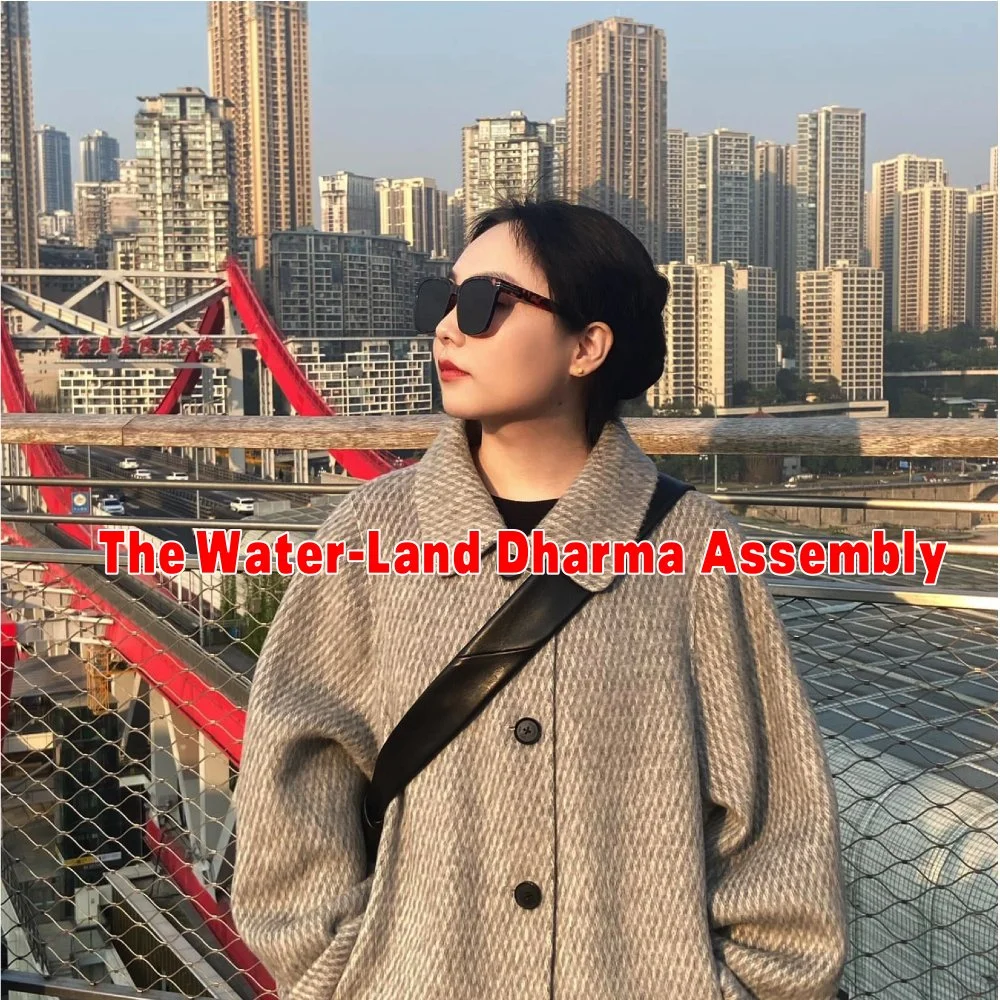

I am thrilled to present a project that explores the relationship between rural and urban areas, public spaces, and the Yangtze River in Chongqing, China.

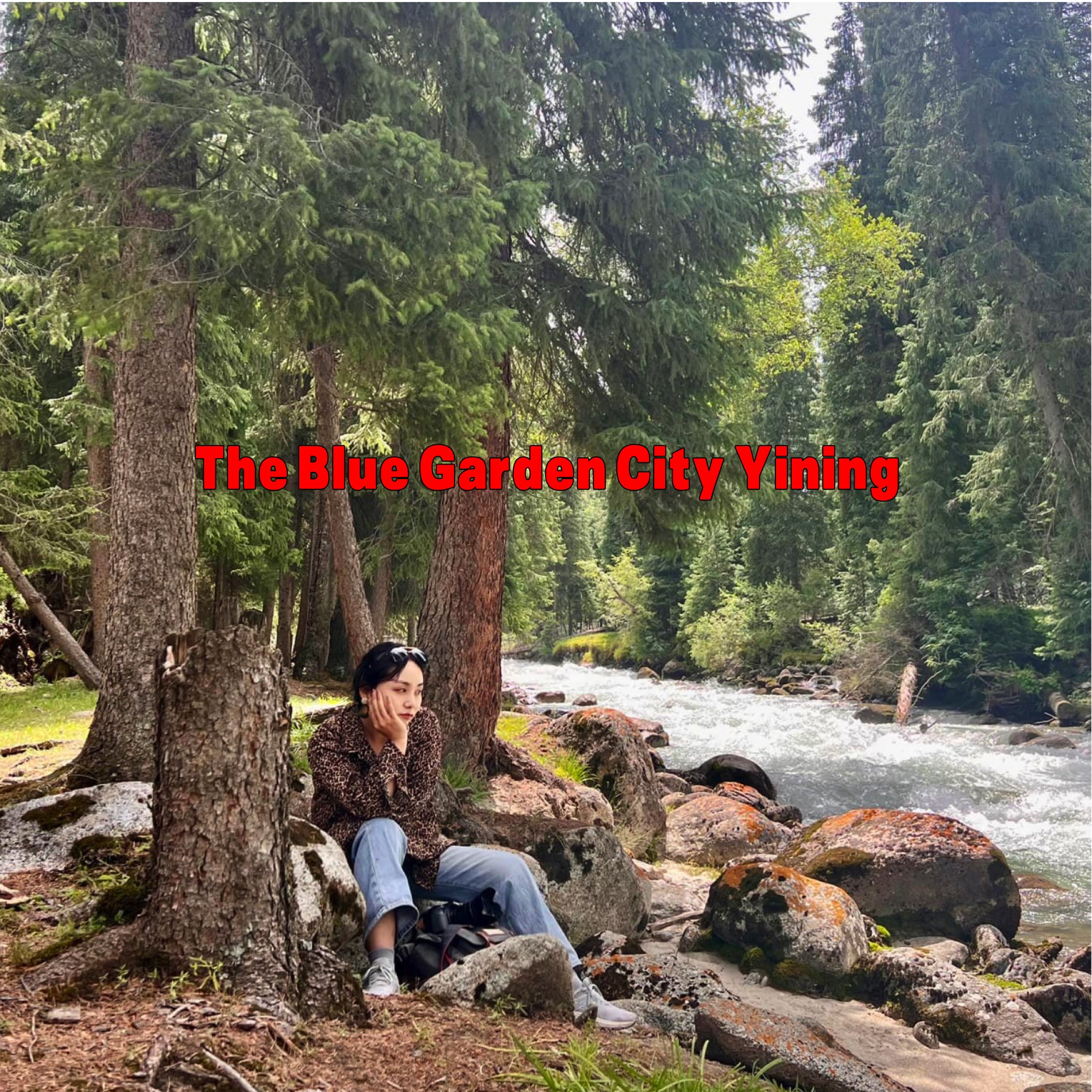

[The Blue Garden City Yining]

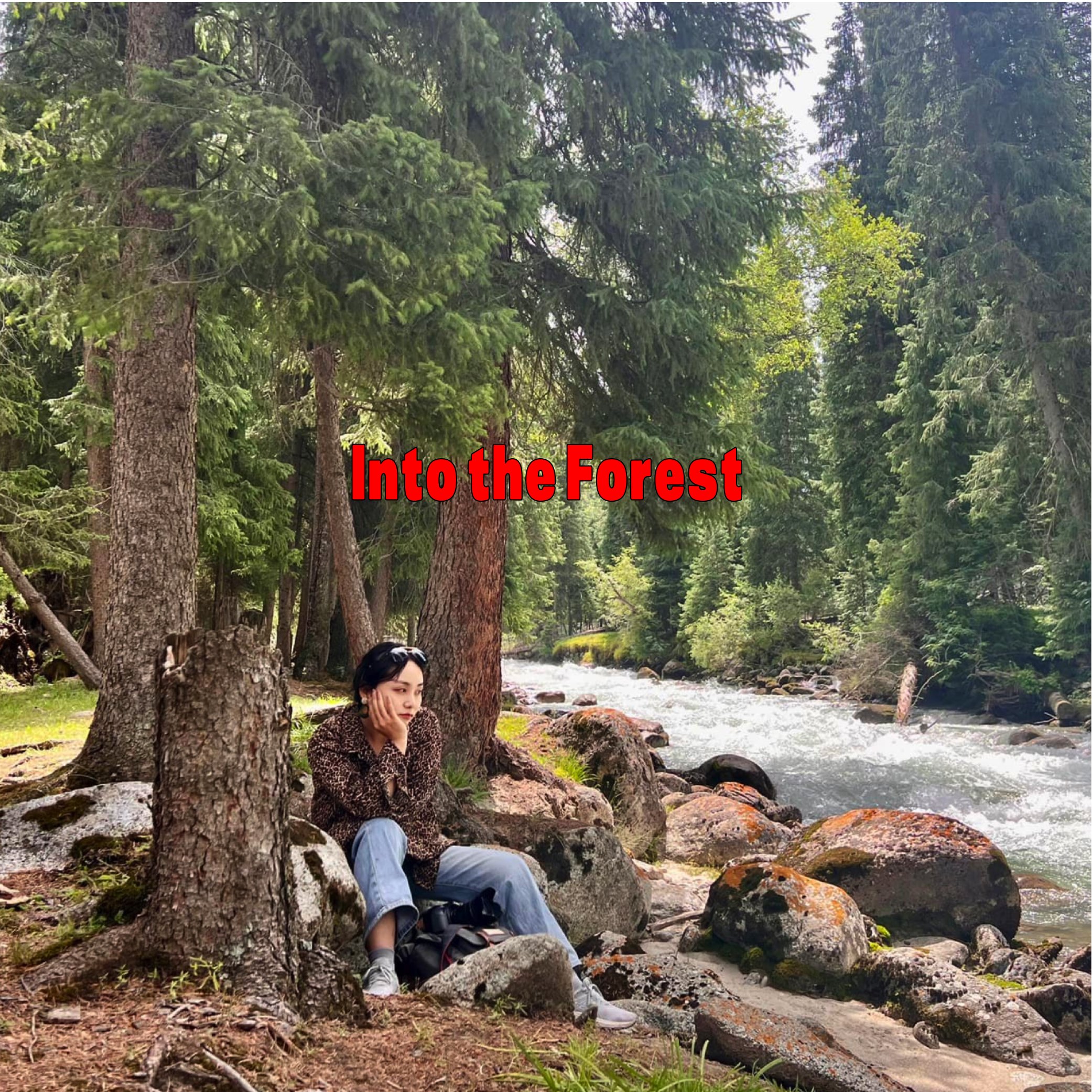

I was born in Xinjiang, China, a place of beauty and mystery, where I joyfully spent part of my childhood. As the sun rose and set, I gazed upon the land that had nourished my life, feeling a sense of awe and gratitude.

I have constantly been on the move, hastily packing my bags, feeling disoriented and uncertain about my identity and life's path. Little did I know that this nomadic existence would inadvertently expose me to the transient nature of life. Living amidst the bustling metropolises, my surroundings have become a cacophony of imposing skyscrapers, the ceaseless commotion of the masses, and the noxious fumes of vehicular emissions. There have been innumerable occasions where I failed to be truly moved by anything. It has been too long since I last paid attention to the gentle mooing of cows, beheld the majestic wingspan of an eagle soaring overhead, or savored the delicate scent of ripened fruits dangling from tree branches. It was during this realization that I made the resolute decision to return to Xinjiang.

Carrying my lemon-yellow suitcase, I embarked on a journey aboard the green train, traveling from the southwest to the northwest. Peering through the train's windowpane, I bore witness to a captivating metamorphosis of the landscape. The previously lush emerald foliage gradually gave way to a vast expanse of desert terrain, while the previously overcast sky revealed its vast and expansive nature.

Xinjiang, geographically divided by the Tianshan Mountains, comprises both northern and southern regions. The northern part is renowned for its majestic mountain grasslands and alpine lakes, while the southern part stretches extensively, characterized by deserts and the Gobi. I spent my childhood in the North, which resonated with a strong influence of Russian culture. Many would often express that the South felt like a completely different world.

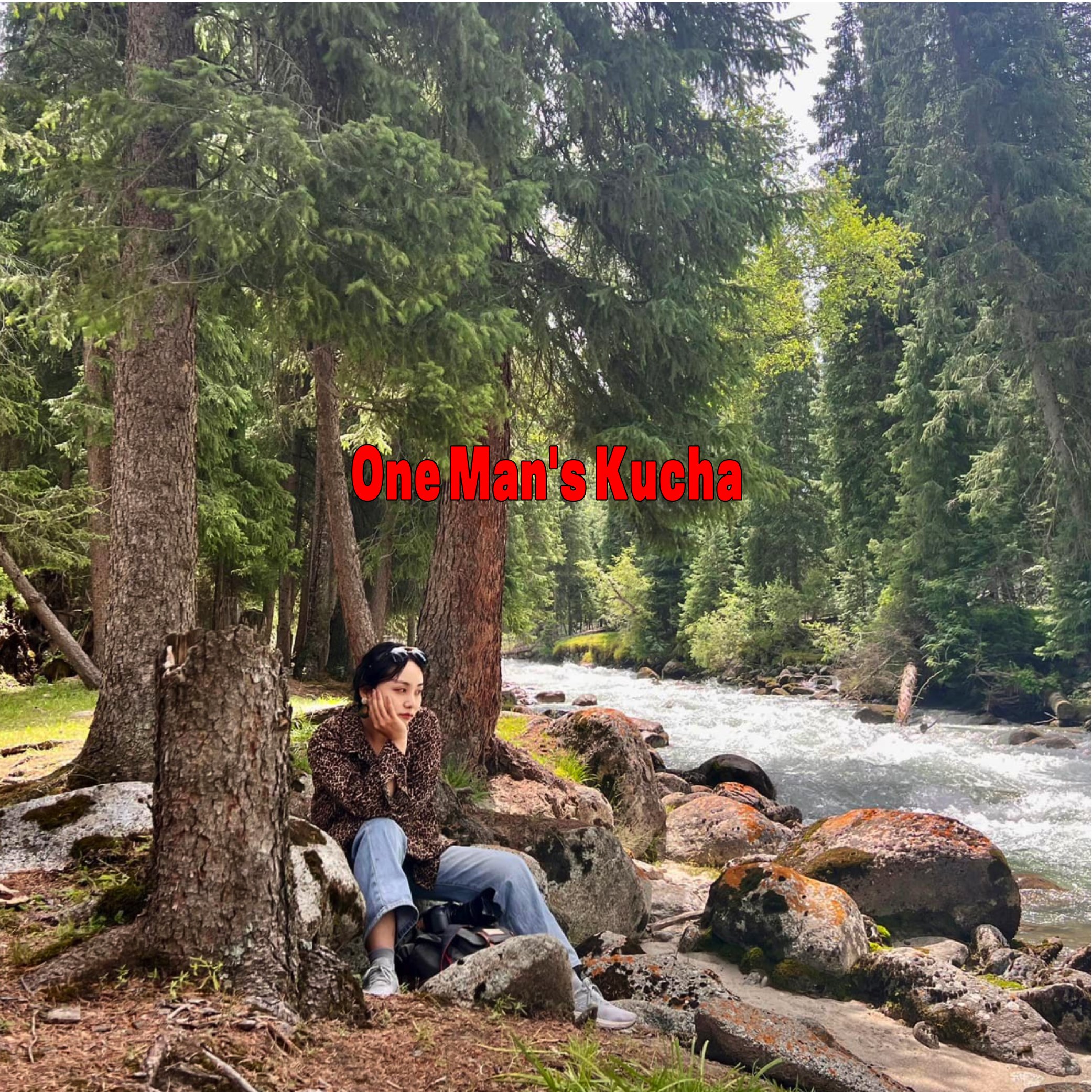

During my time at Xi'an International Studies University, I enrolled in a Hindi Chinese translation course. In this class, the professor explored the significant contributions of Kumārajīva and Xuanzang in translating Chinese Buddhist scriptures. Kumārajīva, hailing from Kucha, a region in southern Xinjiang, and Xuanzang, who embarked on an arduous journey from Chang'an (modern-day Xi'an) through the southern part of Xinjiang to India in pursuit of Buddhist scriptures.

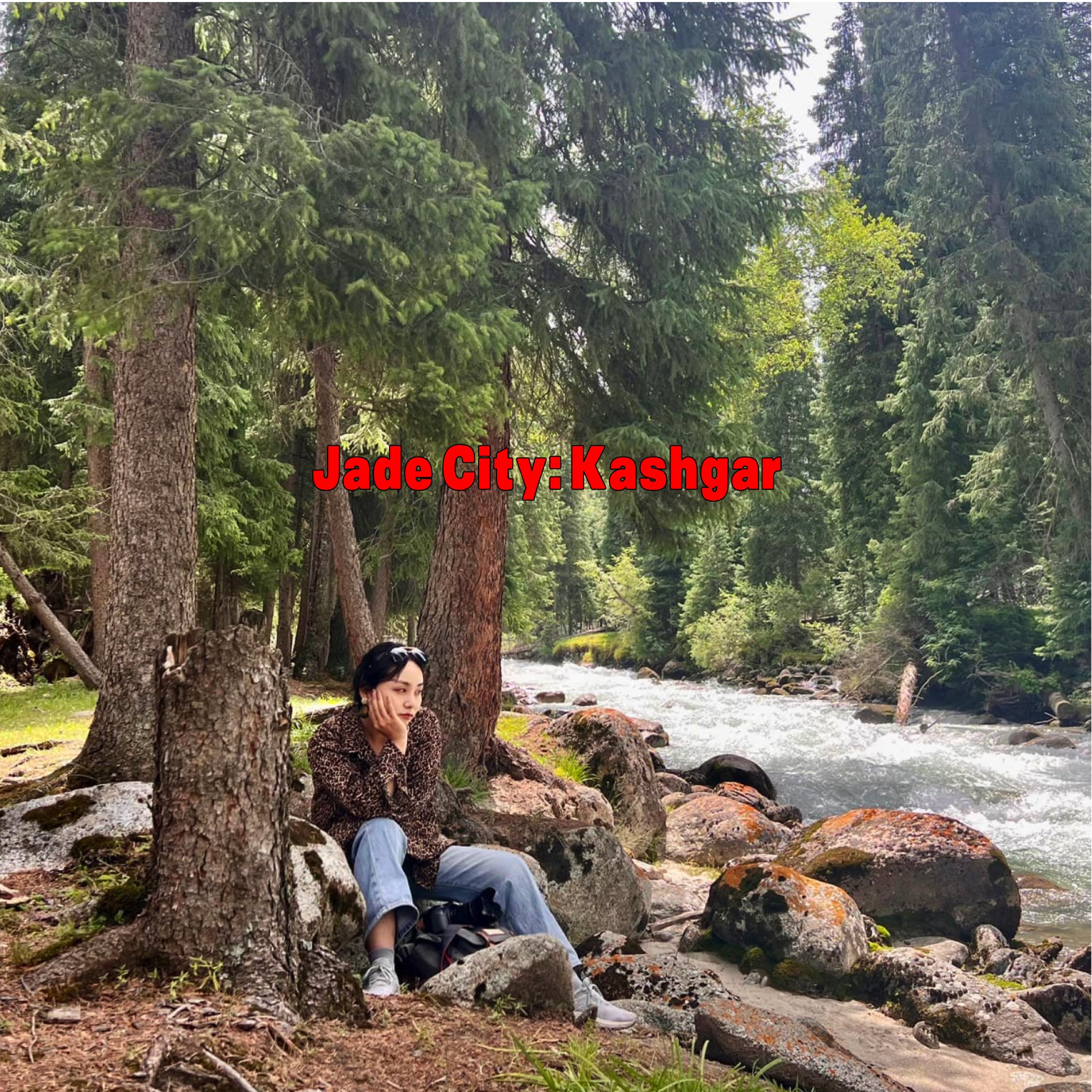

This journey led me to explore the southern regions of Xinjiang, including Kashgar, the Pamir Plateau, Shache, and Kucha. My spirit danced with excitement as I set foot on this southern land, knowing that legendary figures like Kumārajīva and Xuanzang once walked its paths. Wandering through the alleyways, passing by the vibrantly colored doors of houses, I unknowingly entered the secret garden of my heart, where vibrant hues shimmered under the brilliant sun's rays. Occasionally mistaken for a Uyghur girl by the locals because of my appearance, their perception swiftly changed upon hearing me speak.

After exploring the southern regions of Xinjiang, I returned to my birthplace, Yining, in the North. It's a charming blue city, where the scent of daleba permeates the air, and the melodious sounds of an accordion gracefully drift with the summer breeze.

Riding a blue bike through the crowded alleys, I chased the sunset, chatted with a Russian aunt about the peculiar weather, and attended a sunset wedding. These experiences awakened me and brought me back to my roots, reconnecting me with the land.

Looking through my photos of the landscapes, architecture, music, bazaars, and streets, I feel a sense of warmth and nostalgia. I hope that you too can experience the hot and obstinate beauty of the secret garden through my eyes and feel the same connection to the land that I do.