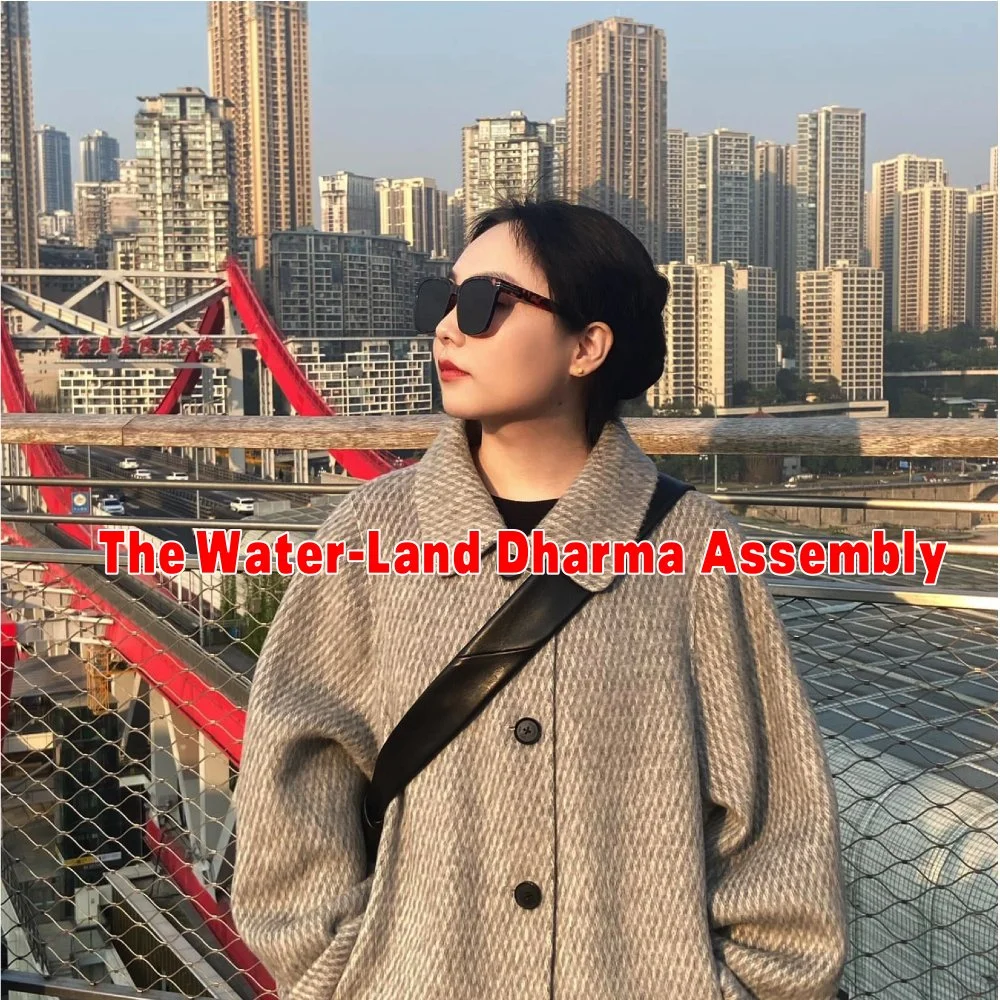

My City: A Chongqing Story

The Voice in the Stone

These mountain stones possess a spirit. They comprehend human words and are fond of their own murmuring. The sounds of wind, of rain, and of the chisel's clink have, over long days, been inscribed within them.

The day I went to see the Yuanjue Cave on Baoding Mountain, the sky was a pale, ashen grey. Bamboo leaves rustled along the path, as if yielding passage to visitors. The entrance was not large, rather unassuming, like the back door of a family home. As I leaned in, a cool air rushed to meet me, carrying the smell of damp stone and the fragrance of aged sandalwood, a curiously delightful aroma.

This cave was hewn by the monk Zhao Zhifeng during the Southern Song dynasty. Elders tell that Zhao was originally a son of the Zhao family in Miliang. At five years old, while other children were still catching fish and shrimp, he was sent into the mountains to devote his days to chanting sutras and mantras. At the age of sixteen, he set out on an unexpected journey west to Mimou Town, a place renowned as the dharma seat of the eminent monk Liu Benzun from a previous generation. This journey was like a scholar's pilgrimage to the imperial academy. He was seeking true roots and deeper mastery.

Returning, he was a changed man. A vow took form in his heart, to raise a Benzun Hall and proclaim the dharma of Liu Benzun. The mountain remained, but by his hand, its very name was transformed to "Baoding," or "Treasure Cauldron." The name was profoundly apt, for the mountain resembled a great ritual vessel, capable of holding all human prayers and refining earthly afflictions.

The sight within the cave was singular. Upon entering, the world plunged into darkness. After a moment's pause, the void gradually gave way to form. A light from a sky-window above leaked down, falling as if guided, squarely upon the Buddha's face. The old saying, "The Buddha's light illumines all," manifested here as tangible truth. Motes of dust drifted and danced in the pillars of light, like a host of minute living creatures conducting a solemn ritual.

Three great Buddhas sat in serene majesty at the centre, eyes lowered, their countenances possessed of a sublime dignity. Though carved from cold, hard stone, their robes were chiselled into folds as soft as silk, so deep and layered they seemed as if they might flutter in a breeze. I paused for a closer look at Vairocana Buddha's hands, formed in the Anjali mudra before his chest, with fingers slightly curved as though cupping infinite wisdom. Though made of senseless stone, those carved fingers seemed more expressive than those of a living person, a fusion of stillness and movement, of tenderness and unyielding strength.

There, directly facing the three Buddhas, knelt a single bodhisattva. Two knees were grounded, her body inclined slightly forward, as if straining to catch every syllable of a revelation of utmost gravity. This was the "Dharma-Inquiring Bodhisattva"—for should any of the twelve assembled Bodhisattvas of Perfect Enlightenment encounter difficulties in their cultivation, it was she who would seek enlightenment from the Buddha on their behalf.

Her placement was so artful, neither obscuring the main Buddha yet herself becoming a scene of its own. Head bowed, eyes lowered, lips gently closed, only her palms pressed together radiated her utmost devotion. Her demeanour of rapt listening seemed as if she would absorb every word the Buddha spoke, to later share with all. Her stone fingers, curved and poised almost but not quite touching, captured and suspended a moment of devout inquiry, crystallising it for eternity. I was suddenly reminded of my grandmother offering incense before the Buddha—the same bowed head, the same silent reverence, her entire being speaking volumes. So, the Buddhist realm too accommodates such human gestures.

Along the two sides were arranged the Twelve Bodhisattvas of Perfect Enlightenment—Manjushri, Samantabhadra, Maitreya, and the others—each named as set forth in the Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment, each distinct in spirit and demeanour. One of them, with arms relaxed and a hand resting lightly on one knee, resembled not so much a deity enthroned upon a lotus as a mountain monk, taking his rest on a rocky ridge after a morning's labour, his whole being pervaded by an air of untroubled ease. So ingenious was the conception that the artisans had chiselled into being not mere statues, but a solemn assembly whose discourse had endured, undispersed, for seven hundred years.

Most intriguing was the alms-bearing monk hidden quietly in a corner. Especially after rain, one could hear the plink-plonk of drops falling into his stone bowl, a clear, ringing tone that carried far through the silent cave. Following the sound, you would find only water dripping from a loong's mouth on the rock wall, falling precisely into the bowl only to vanish in an instant. The sound was clear and near, yet the water itself was elusive, which was a marvellous thing.

Later, a guide explained that this was an ingenious mechanism designed by artisans seven hundred years ago. Rainwater seeped from the cave roof, channelled through the stone loong's body to its mouth, each drop like a pearl spat by the loong. The pearl fell into the bowl with a chime clear as a bell, then was quietly guided through the hollow arm of the monk statue into a covered conduit. An entire water system, concealed without a trace, leaving only a few ringing notes in the ear.

The ancients, in carving their statues, sought to deliver all beings—even the rainwater.

Several elderly women entered the cave to pray. Their movements familiar, they kowtowed and could be heard murmuring everyday concerns: "Bodhisattva, bless my grandson to enter university," "Let my daughter-in-law bear a son." The stone bodhisattvas listened, unbothered, still sitting with gentle grace. It seems that in saving beings, they make no distinction between great matters and small.

Emerging from the cave, I found the sun already setting. Looking back, the entrance resembled a half-open Dharma eye, gazing ambiguously upon the human world. A mountain wind swept by, setting the bamboo leaves rustling once more, but this time not as a farewell, only as if murmuring to themselves.

On Baoding Mountain, the statues of the Mingwang still bear fresh chisel marks, as if the artisans had merely downed tools for a midday rest and would return at any moment. Who could have foreseen that the outbreak of war would silence the chinking of chisels so abruptly, the craftsmen dropping their tools to flee into the hinterland, and even Monk Zhao Zhifeng vanishing without a trace?

On the way back, I saw an old farmer resting on a ridge, chewing on grass roots. He noticed me and asked, "Seen the stone cave?" I nodded. He grinned and said, "Monk Zhao knew his tricks, making stone figures fool the living into circling round and round."

His words struck a chord and set my heart itching with wanderlust. Well, if I was already circling, what was a few more miles? I had long heard that the Huayan Cave in Anyue shared the same lineage as Dazu—like sister sites. What sense was there in seeing one but not the other?

So I invited a friend to drive to Anyue in Sichuan Province. The car wound slowly along unpaved mountain tracks, perfect for enjoying the scenery. Outside, old farmers moved slowly through the fields, like figures stepping out of a Song dynasty painting. But this was not the same Song: while the Dazu Yuanjue Cave reflected Southern Song elegance, the Huayan Cave ahead embodied the authentic Northern Song style.

Huayan Cave lies in Chiyun Village, Shiyang Town—a name full of colour. The entrance was broader than that of Yuanjue Cave, with slightly upturned eaves, giving it a temple-like grandeur.

Inside, before my eyes adjusted to the dimness, I was seized by a hazy splendour. Fragments of gold leaf shimmered in the faint light like resting fireflies; patches of bluish-green resembled frost-touched autumn leaves, and areas of cinnabar red glowed like fading sunset clouds. These colours, applied over several dynasties—likely starting in the Northern Song, with later devotees from the Ming and Qing adding their own touches—had now faded, revealing the gentle, warm stone beneath, more appealing than if it were new.

Foremost to command awe was, naturally, Vairocana Buddha. As always, the Buddha gazes down upon all living beings, yet remains in eternal silence. The stone robes flowed naturally, like water frozen in rock. The sash across his abdomen was tied in a neat figure-eight knot, hanging perfectly straight. On either side, Manjushri's green lion and Samantabhadra's white elephant were particularly vivid: the green lion turned its head with a twist, tongue lolling as if ready to leap down; the white elephant coiled its trunk as though sniffing the aroma of offerings. The artisans, when they chiselled these forms, must have modelled them on the likeness of real creatures from the hills behind.

But what truly held the eye were the ten bodhisattvas standing in a row on either side, each smiling. The craftsmen were bold enough to have them sit with their legs casually crossed, their robes so thin they seemed translucent, as if the jewellery would tinkle in the mountain wind. Their crowns were openwork, finer than papercuts in a woman's window. One wonders how many turns the chisel had to make.

One sat cross-legged, Bianyin Bodhisattva. Locals call her "White-Robed Guanyin." Entirely white, her robes soft as spring water, the edge of her kasaya gently covering her crown. The necklace was interesting: two rows of plump, connecting beads, like strings of dewdrops. Her hands were tucked neatly in her sleeves, resting before her abdomen as if holding a warm stove. Her closed eyes were most moving, eyelids lowered as in light sleep. Villagers say that when they knelt in prayer, they could see her eyelids tremble. Now, barriers keep viewers at a distance, allowing the bodhisattva some peace.

"In earlier years, people even dried baby diapers up there!" An old villager sat on the stone threshold smoking a pipe, smoke curling up. Noticing visitors, he pointed at the bodhisattva's leg with his pipe. Exhaling slowly, he added, "Families used to live in this cave. The daily cooking smoke darkened the bodhisattva's face. Later, the government stepped in and, in the eighties, had the families relocated. Only then did it become clean."

On the north wall, Sudhana's Fifty-Three Pilgrimages unfolded like a comic strip. At each stop, the youth bowed reverently to seek teachings. Those wise beings wove cloth, caught fish, one even scalded a pig's head—arhats appearing as butchers, the Dharma never separated from worldly awareness.

Suddenly, fragments fell rustling from above. Looking up, I beheld the cinnabar-character "Om."

The character was solidly written, neither floating nor restless, seeming to anchor all the flowing light in the cave.

On the main wall were carved two lines of verse. The stone frame was square, the chisel marks rough and deep, the characters somewhat blurred by wind and rain. Studying them, I made out: "If one wishes to understand / All Buddhas of past, present, and future / One should observe the nature of the Dharma realm / Everything is created by mind." An old saying from the Huayan Sutra.

Pilgrims paused to recite it. Though they might not grasp the deeper meaning, their hearts felt clearer. And that was enough. Sutras are not meant to be explained, but to be understood on one's own.

How long did it take to carve this cave? That's hard to say. Grandfathers began, grandsons finished. Such things were everyday. It was a fine thing regardless. Whether finished a few decades sooner or later, it was all the treasure left by the ancestors.

Several village women came in to offer freshly picked loquats, placing the yellow fruit on the altar. They prayed as though chatting: "Bodhisattva, try the new fruit, it's so sweet. The children at home can eat half a bowl each."

Incense smoke curled upward, tangling with the flying apsaras' ribbons. The scent of fruit, sandalwood, and smoke merged into a pleasant aroma.

Breathe it in long enough, and it becomes part of life.